Long before his 1,000th win—way before the four national championships, 11 Final Fours, and 82 NCAA tournament game victories—Mike Krzyzewski had us in a bind.

As four of us from The Chronicle’s sports desk walked down Chapel Drive toward the March 18, 1980 press conference at which Duke’s new head basketball coach was to be announced, we ran through the possibilities. Bill Foster had resigned as coach two weeks earlier on the day Duke won the ACC championship, and we figured his popular assistant Bob Wenzel had a shot at the top job. But a “name” coach seemed more likely: maybe Tom Davis from Boston College, or Chuck Daly, a former Duke assistant who had taken Pennsylvania to new heights before moving to the NBA. We bickered, argued and assessed the odds of almost every coach in America other than Dean Smith himself.

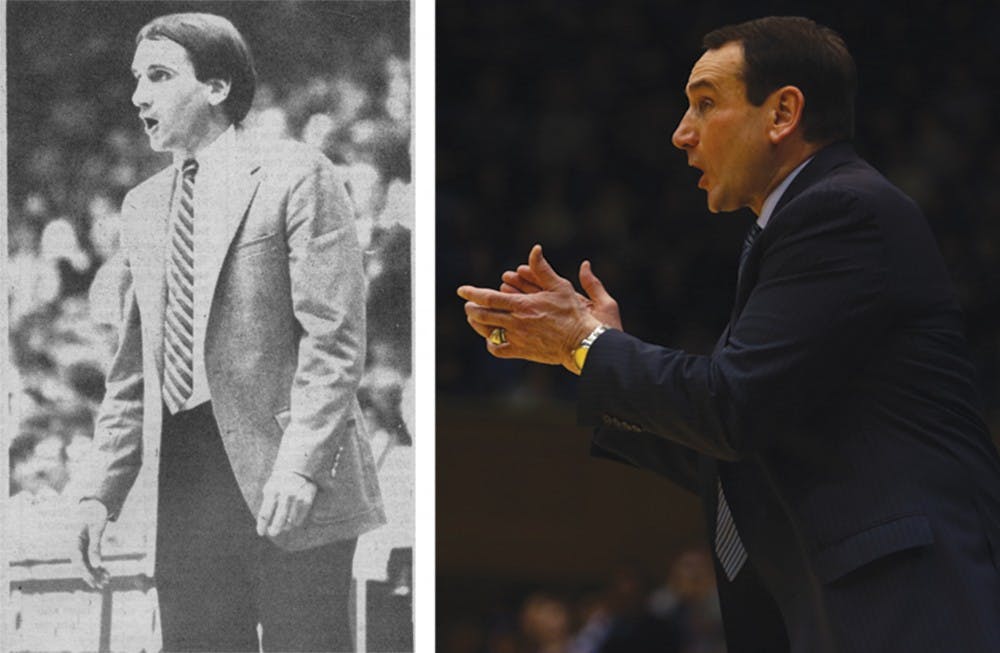

One name that did not come up was Mike Krzyzewski. I can say that with certainty, because none of us had ever heard of him until the moment athletic director Tom Butters took to the microphone with the startling announcement that the anonymous young guy in the camel-colored jacket was to be the new Duke University basketball coach.

The press conference was late in the day, shortly before our deadline for the next day’s paper. Yet we knew literally nothing more about Krzyzewski than what was said at the press conference. He had taken a moribund program at Army to 20-win territory and made the NIT. In his most recent season, though, the team had slipped to 7-19. In that pre-Internet era, there was no way of sounding suddenly smart about something you knew nothing about. When we got back to the Chronicle office, we found nothing about Krzyzewski in the basketball guides strewn about. A guy on the news desk had a high school buddy at West Point, but when we called, the cadet who picked up the hall phone didn’t know anything about Krzyzewski.

This was the guy Butters selected?

The headline in the next-day’s Chronicle reflected our surprise at the choice, with an allusion to his alphabet soup name: “Krzyzewski: This is Not a Typo.” We included a helpful, albeit incorrect, pronunciation key in the article: “Kre-shev-ski.” At least we did better than the AP, which offered: “Kre-ches-skee.” (If today’s students find it hard to fathom why the pronunciation wasn’t obvious to us, just try asking Siri to name Duke’s basketball coach.)

As Coach K’s legend has grown during the last 35 years, some have assumed he essentially created Duke basketball. In fact, Duke was a recognized, though inconsistent, national power before he arrived. Indeed, just three days before the press conference announcing Krzyzewski’s hiring, Duke’s season had ended with a heartbreaking loss to Purdue in an NCAA Regional Final. Two years earlier, the Blue Devils had made it all the way to the national championship game.

Given that history, many were disappointed Duke had selected such an obscure coach. But there were hopeful signs. Krzyzewski had the strong endorsement of his former college coach Bob Knight, a canny evaluator of coaching talent. Butters, not known for hyperbole, expressed “no doubt” that he had found “the brightest young coaching talent in America.”

Krzyzewski understood that he wasn’t a household name, and he worked hard to remedy that by making himself broadly available, even to student reporters. He was very clear about his coaching philosophy—which is largely unchanged—and he was funny. Asked about his last name, he quipped, “You should have heard it before I changed it.” His West Point pedigree drilled into him something many coaches never develop: pride in an institution, not just in a basketball program. He seemed genuinely humbled to be a custodian of the tradition and values of Duke. In those early days, I could not have predicted the kind of coach he would become, but it was easy to predict that he would not bring scandal or embarrassment to the university. He worked the media, student groups and community organizations, and before he coached his first game, he had built a solid reservoir of goodwill and hope.

He would need it. Foster, his predecessor, had left a legacy of ACC championships and high national rankings, but he had not left a recruiting class. Star seniors Gene Banks and Kenny Dennard led a team with little depth to a 17-13 record in Krzyzewski’s first year, highlighted by a dramatic win in Coach K’s first home game against North Carolina.

Although disappointed by the first season, Duke fans were energized by the knowledge that Coach K was in the hunt for some of the top recruits in the nation. But all the big names, including Chris Mullin, went elsewhere. Coach K started his second year with an extremely thin roster, and the results reflected it.

The season opened with four losses in five games, the worst start in school history. Right before the December, 1981 exam break, Duke was humiliated by Princeton, 72-55. Krzyzewski was reeling. “This is the worst I’ve felt after a game in my seven years of coaching,” he said after the game. “We were embarrassed. It was a total collapse.”

The Princeton game, arguably the nadir of Krzyzewski’s coaching career, spawned an unusual meeting in the Chronicle offices. We felt we needed to formally discuss the rising chatter, on campus and nationally, about the decline in the team’s fortunes. Specifically, we needed to discuss whether we believed Krzyzewski was up to the task of leading a big-time program—a question that increasing numbers of observers were starting to doubt. One by one, each member of the sports department offered a perspective, commencing a heated discussion.

In the end, despite the struggles on the court, the group was persuaded by one remarkable fact: the criticisms of Krzyzewski were almost all based on his record, from people who didn’t know him. Those who worked with him daily— his players, his assistant coaches, athletic director Butters, sports information director Tom Mickle and his deputy Johnny Moore—universally thought he was not just solid, but extraordinary. By the meeting’s conclusion, our consensus was that Krzyzewski was a good man who was making progress. He deserved more time. While anyone was free to write what he or she wanted individually, there would be no editorial voice of The Chronicle calling for a new coach that year.

It didn’t matter, of course. The only opinion that counted was Tom Butters’, and he never wavered, publicly or privately, from his opinion that he had the best young coach in America. Not during that 10-17 season in 1981-82, nor during the 11-17 season that followed.

What we didn’t know the day of that Chronicle meeting was how close Krzyzewski was to assembling the pieces of his first great team. The following month, he enticed Jay Bilas to commit to Duke. Then Mark Alarie. Johnny Dawkins signed on next, and David Henderson rounded out the best recruiting class ever at Duke, at least until 2014. That group struggled in its first year—Krzyzewski’s third. The following year, however, they led Duke back to the NCAA tournament, starting a string of 30 tournament appearances in 31 years that made the anonymous guy in the camel-colored jacket the most successful college coach in history.

—By Andy Rosen, 1980-81 Chronicle Co-Sports Editor (with Dave Fassett)

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.