Although offering loans places Duke in a minority among elite universities, the University stands behind its financial aid policies.

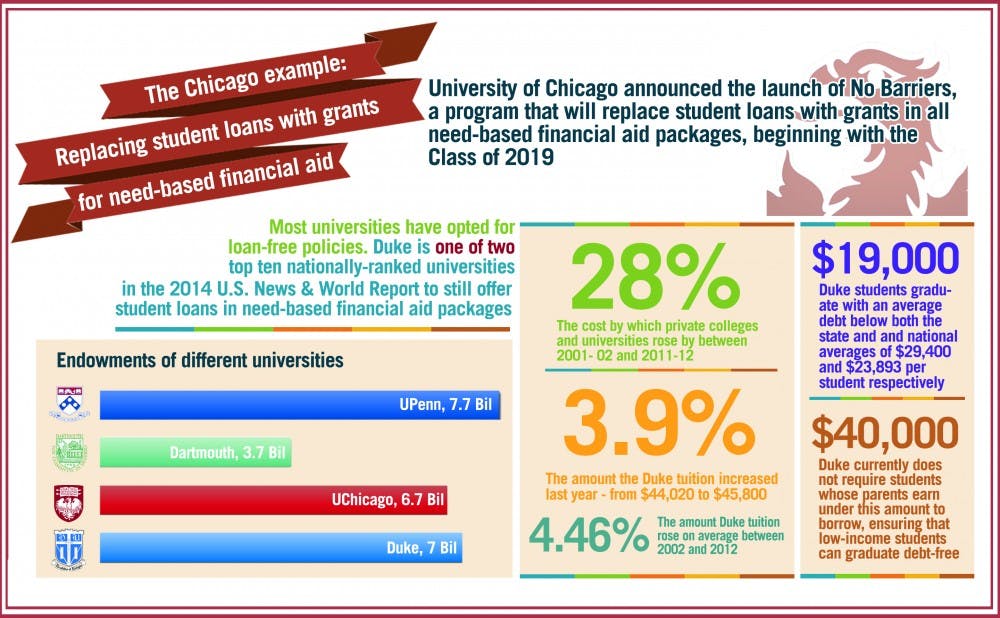

Several weeks ago, the University of Chicago announced the launch of No Barriers, a program that will replace student loans with grants in all need-based financial aid packages beginning with the Class of 2019. Its new commitment to eliminating loans leaves Duke and the California Institute of Technology as the only two top-10 universities in the 2014 U.S. News and World Report rankings that still offer loans in need-based financial aid packages.

Duke currently has policies in place to limit the loans given to any student in one year and to keep low-income students from taking loans altogether. Although the University has considered going completely loan-free in the past, there remain significant financial barriers to getting rid of student loans, Alison Rabil, assistant vice provost and director of financial aid, wrote in an email Saturday.

"It's an expensive proposition," Rabil wrote. "And we believe that the policies we have in place minimize the debt a student has to incur while he or she is here."

'An expensive proposition'

But going loan-free is not entirely out of the question, Rabil added. The ongoing Duke Forward capital campaign, which aims to raise $3.25 billion by 2017, stands to raise more than $400 million for financial aid, she said—noting that whether Duke will consider a no-loan policy after the campaign remains a question for President Richard Brodhead and Provost Sally Kornbluth.

The University of Chicago is also in the middle of a capital campaign, aiming to raise $4.5 billion—part of which will be used to cover the cost of transitioning to the loan-free policy. In addition to the fundraising campaign, the university will also draw on its endowment of $6.7 billion, which is roughly on par with Duke's $7 billion.

Beginning with Princeton University's decision to go loan-free in 2001, many top tier colleges and universities have adopted no-loan policies over the past decade—including Harvard University, Yale University and Columbia University. Although these institutions have significantly larger endowments than Duke, other universities with comparable or smaller endowments have also opted for no-loan policies in recent years, including the University of Pennsylvania and Dartmouth College—with endowments of $7.7 billion and $3.7 billion respectively, according to the 2013 National Association of College and University Business Officers Commonfund study of endowments.

When Duke changed its financial aid policies in 2008 to offer no more than $5,000 in loans to any student in one year, the administration considered all possible scenarios—including going loan-free. Rabil noted that it was projected, however, that millions of dollars in additional aid would be required.

"That translates into a very large influx into endowment when you're only spending a small percentage of the interest earned on the endowed funds," Rabil wrote.

A number of universities have rolled back on no-loan policies in recent years after they proved too costly. Williams College eliminated student loans in the 2008-09 school year but revoked its no-loan policy three years later, and the University of Virginia rolled back its policy of no loans for low-income students after the cost of providing grants nearly quadrupled.

A number of smaller schools have maintained their no-loan policies despite these financial challenges, including Amherst College and Davidson College. Several other schools have a policy similar to Duke's, with no loans for low-income students—including the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Currently, UNC is spending more than it has fundraised from private sources on the Carolina Covenant program to provide loan-free financial aid packages to low-income students, Shirley Ort, associate provost and director of Scholarships and Student Aid at UNC, wrote in an email Friday. Whereas the Covenant's endowment is only about $6 million, $150 million would be required to fully fund the program—a long way off.

"We started the program without having raised all the money we needed first," Ort said. "Had we waited for that, we may never have started the program."

Soaring tuition and student debt

The University of Chicago's announcement comes at a time of rapidly rising tuition and student debt. From 2001 to 2011, the cost of private colleges and universities rose by 28 percent, according to a report by the National Center for Education Statistics. Tuition at Duke increased 3.9 percent from last year—from $44,020 to $45,800—and on average, rose 4.46 percent per year between 2002 and 2012.

Rising costs have imposed greater financial constraints on both parents and students—many of whom incur considerable student debts during their four years at college. Currently, students graduate with an average debt of a little less than $19,000, Rabil said—a figure below both the state and national averages of $29,400 and $23,893 per student respectively, according to the Project on Student Debt.

"We believe the amount is manageable, especially since the vast majority of the loans are subsidized federal loans that do not accrue interest while enrolled and have income-based repayment options," Rabil wrote.

Students, however, have pointed out that the burden of student loans remains considerable for many.

"When people graduate, they graduate with all that debt, and if they can't find a job, then they're screwed," senior Chelsea Zhou said. "I'm lucky because my parents are helping but some people aren't so fortunate."

Sophomore Tina Chen said her financial aid package this year is less generous than that of the 2013-14 academic year, when Duke had attempted to match financial aid packages offered by other universities.

"Once you're securely nested into Duke, they change your financial aid package to match their own calculations," she said. "I guess it makes sense that they do that, but at the same time, I wished they'd let me know in advance."

Duke currently does not require students whose parents earn less than $40,000 a year to borrow, Rabil said. By ensuring that students graduate debt-free, no-loan packages target low-income students, who might otherwise hesitate to enroll in costly private institutions.

Although loan-free policies target low-income students, the cost of providing loan-free financial aid also rises with the number of low-income students enrolled, Ort noted.

Limitations of loan-free policy

With a loan-free policy in place, students may still have to borrow in order to cover their family's Expected Family Contribution, Rabil noted. The EFC, or the portion of total costs which families are expected to pay, is calculated by individual universities based on families' different financial situations. This amount, however, sometimes exceeds families' actual capacity to pay.

"Students will still borrow to cover their parents' contribution so the graduating debt even at a place like Harvard where there is the most generous financial aid program with no loans is still $5,000 to $7,000 per student," she wrote.

Kathleen Zhou, a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania—which has a no-loan financial aid policy in place—called the policy "bogus" and added that her family's EFC was so high that borrowing was unavoidable.

"If they had given me loans immediately in my freshman year, I probably wouldn't have chosen to attend," she said. "But really seeing the amount of loans I'll need later, in the long-run, the end would have been the same regardless of whether or not Penn was loan-free."

Whether EFC is perceived as excessively burdensome or reasonable can often depend on students' individual backgrounds and lifestyles, Chen noted.

"Creating a financial package based on all of the different lifestyles of Duke students is very hard," she said. "I guess money doesn't really matter—it's how you change your life around the money that matters."

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.