The first edition of “Leaves of Grass” was published in 1855 and did not include the author’s name on the cover page, but rather a frontispiece of Walt Whitman in working-class garb and a titled hat, hands tucked into his pockets. This claim of authorship answers the question, “Who wrote this?” not with a formal name, but with a semblance of tangibility. Later editions would include his name on the cover, but always his nickname, “Walt,” as opposed to his birth name, “Walter.” Whitman attempted to undermine the social constructions for labeling his own identity in relation to his work, and, in doing so, created a new iteration for the role of the poet.

In revisiting my own edition of “Leaves of Grass,” which features an image of an older Whitman, I can’t help but be reminded of social media profiles. Like the cover page of Whitman’s collection, profiles often contain an image of the user alongside their username, a declaration of identity in an informal manner: this is who I am. In Homer’s “The Iliad,” characters are introduced with epithets and elongated descriptions of their lineage, but with the prominence of social media, I am more likely to identify my friends online by their Twitter handle than by their legal name.

However, this new form of identification does not defy social conventions, but replaces one conventional format with another. The notion that 160 characters, a collection of ‘likes’ or a profile picture can encompass the entirety of someone’s identity is as incomplete as is expecting an epithet to. Yet, these new formats are ripe with the same opportunity to redefine that was present in the frontispiece image of Whitman.

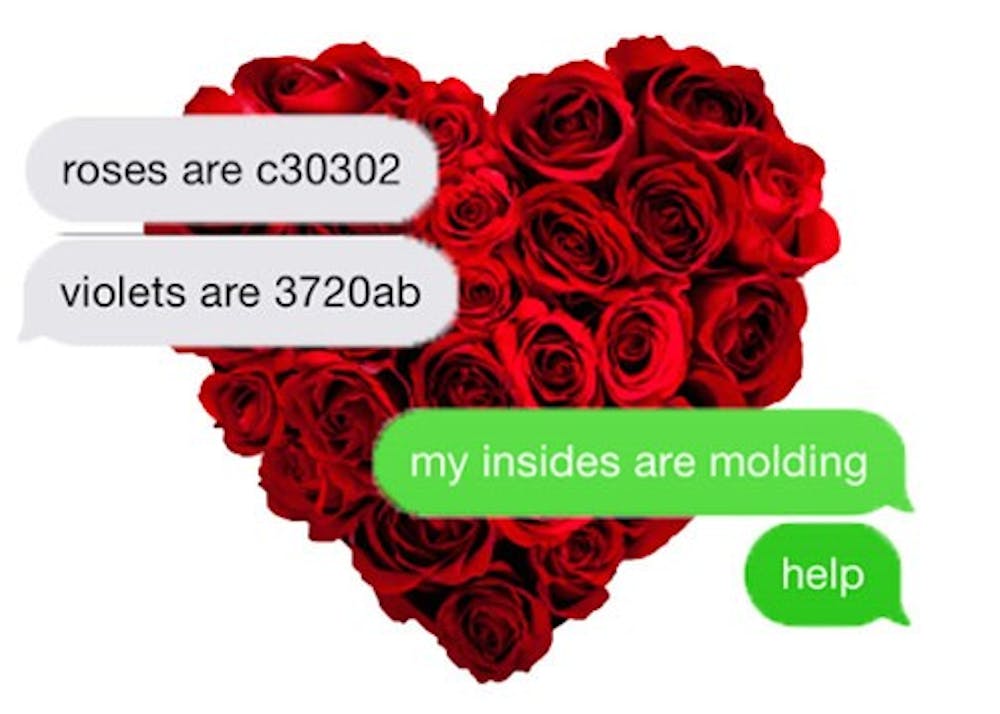

What is most astounding about Rogggenbuck’s online presence is that he is just one example of many efforts to define both the poet and poetry in the digital age. Sites like INTERNET POETRY and The Jogging feature creative works in Internet formats, such as screenshots, Tweets, Google searches or memes. In doing so, these sites facilitate new possibilities for formats typically used to display trivialities; they introduce poetry into the realm of the Internet.

Moreover, they introduce the contemporary poet into the realm of the Internet. A cursory glance at the INTERNET POETRY site reveals that authorship is no longer cited by legal name, but by Tumblr URL. Clicking on these various URLs reveals hundreds of different authors who define themselves in a multitude of ways—by usernames, by images, by preferences, by locations and by generation.

Roggenbuck also feels similarly inspired by both Whitman and the possibilities of the Internet. In his video manifesto, “AN INTERNET BARD AT LAST!!! (ARS POETICA),” he states, “Walt makes you step back and say the world is wonderful, this whole thing that is going on is wonderful. Pay attention to what is going on with life. When Walt Whitman did that to me, there was a fire lit up inside of me, from then on, that is my purpose in life, to bring that about in other people, to point my finger at the moon for other people. The Internet is the most effective finger pointing at the moon that we have ever had.”

In revisiting Whitman, I can’t help but feel like he might agree:

“The question, O me! so sad, recurring—What good amid these, O me, O life?

Answer.

That you are here—that life exists, and identity,

That the powerful play goes on, and you will contribute a verse.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.