A recent rift between the Food and Drug Administration and a private genomics company has sparked a debate about whether or not non-medical companies should offer customers a health analysis.

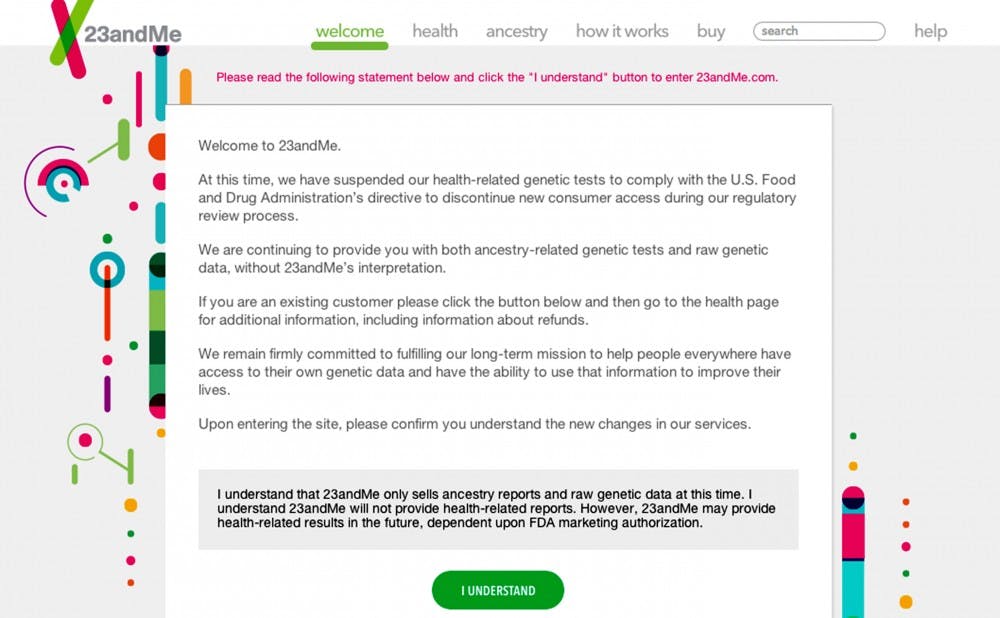

23andMe is a private company that analyzes DNA for genetic markers of disease, providing customers with a wide range of genetic information—such as propensity for disease, and data about their ancestry and genealogical roots—for a fee. The company has recently come under the scrutiny of the FDA for providing health assessment information, such as relative risk for Alzheimer’s or other diseases, without clearance from the FDA. The FDA issued a cease and desist letter in late November, and the company has since agreed to stop providing any interpretive information beyond raw genetic data.

Genomics experts at Duke diverge on whether or not 23andMe overstepped its boundaries, but see the value in getting genomics information out in the public sphere.

The FDA is concerned because 23andMe was providing medical information even though they are not approved to practice medicine, said Huntington Willard, director of the Duke Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy.

“23andMe is trying to have the best of both ways—to say they are not practicing medicine and then everything they write makes it seems like they are practicing medicine,” he said.

Willard said what 23andMe does ends up resembling a diagnosis.

“Both as a customer and as a knowledgeable customer, I think they had crossed the line,” Willard said.

Willard explained that he understands the importance of the data provided by 23andMe but believes that the nature of the information might induce customers into thinking that the information has direct medical value.

“There’s value in that in terms of engaging the population, getting people more knowledgeable and getting people more comfortable with the concept that we all have bad variants in our genome,” Willard said. “But getting people to think that that has real medical importance at this stage in the game is probably premature.”

But the 23andMe information is in no way meant to give a diagnosis, said Nita Farahany, director of science and society and the Duke Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy.

“It is not intended for or designed to be a diagnostic test and genetic predisposition information doesn’t diagnose you with a condition. All it does is give you some probabilistic information that might guide you down different paths,” Farahany concluded.

But like Willard, Farahany believes that the company is helping in the liberalization of scientific data. They have improved access to personal genomic information and helped educate people about the significance of their genetic data in relation to their health.

She added that the information might help people make good decisions about their health.

“If you find out you have a significant predisposition to deep-vein thrombosis you might want to wear something like supportive socks when you take long flights across the country,” Farahany said.

The FDA might be taking this step because they believe the general public do not have the tools to properly understand the information provided by 23andMe without proper medical consultation, Farahany said.

“Some people are what we call health exceptionalists. [They believe that people] can’t understand what it means, that they are not qualified to receive that kind of probabilistic genetic information that the company 23andMe is providing,” she said.

She feels, however, that the test 23andMe proposes is not any different from other similar devices people use to track their health.

“[It] is just a test tube you spit into and send back and get some information about yourself from,” she said. “From my perspective, this isn’t that different than [fitness] trackers and other types of health trackers that people get real useful data about.”

The test might have significance for some people, said Biqi Zhang, a senior who took the test. She noted that even though she has fun comparing her results for things like ancestry, hair color or earwax type with her friends, she also sees the gravity of learning that someone might be at risk for an incurable disease.

“Having this sort of data is certainly not silly for some, especially those with family history, who may end up discovering that they have increased risk of developing an incurable disease, like Alzheimer’s,” she wrote in an email Sunday. “23andMe does offer consumers potentially life-changing information, so one does have to be informed before purchasing an account.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.