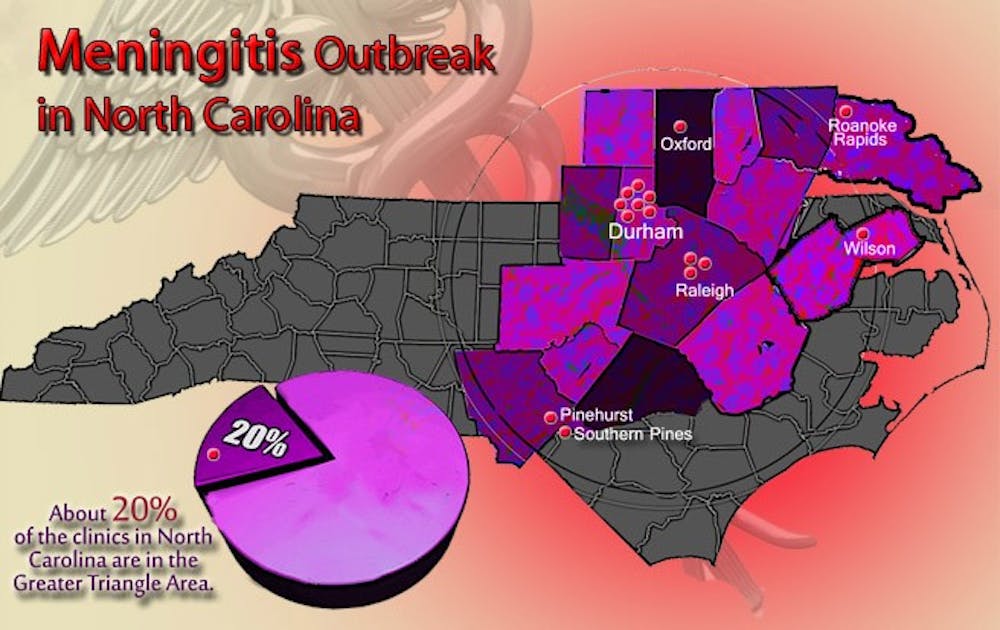

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration labeled 80 North Carolina health care facilities, including seven in Durham, as customers of the pharmacy tied to the ongoing national meningitis outbreak.

Three among those listed—Durham Regional Hospital, James E. Davis Ambulatory Surgical Center and North Carolina Orthopaedic Clinic—are part of the Duke University Health System, but only North Carolina Orthopaedic Clinic used the injectable steroid, methylprednisolone acetate, that was found to be contaminated, said Karen Frush, chief patient safety officer for the Duke University Health System. No DUHS patients have reported cases of meningitis, and the steroid was only used for joint treatments at the orthopedic clinic. No spinal injections occurred, she noted.

Methylprednisolone acetate is a preservative-free steroid that is injected into the lumbar spine or into joints and is used to treat pain, said Richard Drew, associate professor in infectious disease at the School of Medicine. Fungal contamination of the product in New England Compounding Center laboratories has led to 424 cases of meningitis nationwide and 10 reports of joint infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control. At least 31 people have died from the outbreak. There have been three reports of infection and one death in North Carolina.

After receiving alerts about the outbreak from the CDC earlier this year, Frush said she and her team called patients—approximately 200 individuals—of the orthopedic clinic who had received steroid injections produced by NECC to inform them of the risk of meningitis. Based on FDA recommendations, patients who had not received the steroid injection but had been treated with other NECC drugs were notified via letter, and a hotline was established for patients to call who had questions or concerns. Approximately 1,200 patients received NECC products within Duke Health System, Frush said.

“We don’t want to unnecessarily worry people, but we do want to use an abundance of caution,” she said.

Because this particular strain of meningitis is fungal and not bacterial, it cannot be transmitted from person to person, making it a “contained outbreak,” Drew said.

“This is a local situation where it was caused by contaminated solutions, and one has to realize that it is and continues to be hospital-acquired infection,” said Dr. John Perfect, chief of the division of infectious diseases. “When we’re dealing with all the hardware, we’re putting in patients, all the antibiotics we use and the resistance they build up, trying to prevent these infections is something we have to do—day in, day out.”

Finding systematic ways to treat patients who are infected in health care facilities can be problematic, and is often uncharted territory, he added.

Perfect, who has worked as a clinician at Duke for 35 years, specializes in patient care for infectious disease and was involved in treating a 2002 meningitis outbreak that affected five patients at Duke, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and East Carolina University.

“I felt like it was Groundhog Day when I first heard about the cases [in the current outbreak],” he said. “My focus is how to get these patients back to their normal health while trying to practice evidence-based material. Then these outbreaks come out where there’s no precedent [for treatment] because we don’t have natural histories of how these things should be managed.”

How to treat such cases is an evolving issue that includes not just physicians and their patients, but also national and state regulations and guidelines, Perfect said. Disputes over drug distribution and compounding is the “raging controversy” underlying the outbreak itself, Drew said. The FDA oversees drug production, but compounding—the combining or altering of drugs—is regulated by states through pharmacy licenses. As a compounding company, NECC is not allowed to manufacture drugs. Instead, it is only supposed to compound drugs on a patient-specific basis after obtaining prescriptions. But the FDA and the Massachusetts health department have both claimed that NECC was operating as a drug manufacturer—it shipped approximately 17,000 vials of its steroid to 23 states without procuring advance prescriptions.

“[NECC] set up trust in the public, and it wasn’t safe,” Drew said. “That’s the underlying story. Not only is this horrible in terms of individual patients, but it has also brought this issue of who manufactures and compounds and who oversees them to light.”

The NECC was shut down by Massachusetts health officials and there will be a U.S. Senate hearing Nov. 15 on state and federal oversight of the company.

Perfect said that for now, he thinks the most pressing matter is patient care.

“When all’s said and done, there’s still a lot of sick people out there,” he said. “Trying to manage that without knowing what the natural history is—it’s tricky. Trying to be consistent at a local and policy level is tricky. There are a lot of people trying to help out on this thing and just like how we respond to Katrina or Sandy, how we respond to this disaster is very important.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.