Nearly two years after its inception, the Arab Spring rages on. Children are dying. Regimes are crumbling. Families are failing. Faced with this reality, first and second generation Middle Eastern immigrants at Duke are left to wonder what is happening to their homelands. Although they live in Durham, they are casualties of events taking place a world away.

The effects of Arab Spring protests still linger in Yemen; another intifada—Arabic for “uprising”—has not yet come to the Palestinian territories, but it may; and though the rebels are gaining traction in Syria, the conflict there does not seem likely to end anytime soon.

With so many different interpretations of the various protests, it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction. It can be even harder to decipher who is right in conflicts that feature so many clashing worldviews.

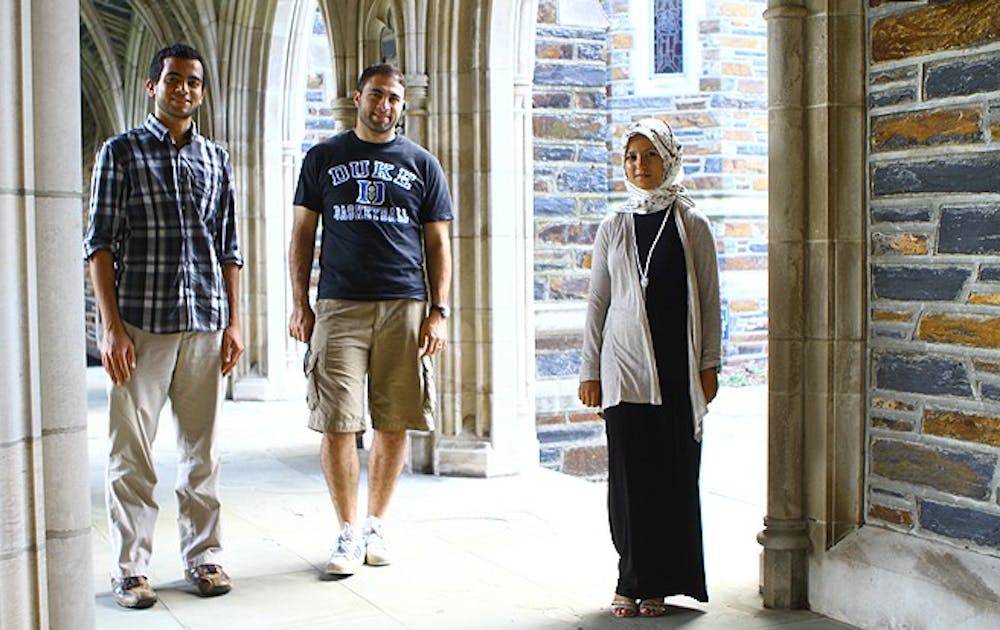

In some cases, including that of Farris Martini, a Duke Law student from Syria, families living in the United States fracture along strict sectarian lines that mirror those of conflicts raging back home.

“The conflict has definitely taken a toll on some familial relationships,” he said. “My father is very active in the opposition and has become essentially estranged from some of his family members who support the regime. His father passed away a couple of months ago, and the unfortunate irony is that my father…would normally have been there during his last days.”

After Martini’s maternal grandfather was interrogated by the Assad regime, his mother’s immediate family fled Syria. Martini’s maternal grandmother had to leave her mother behind, who died shortly thereafter.

Like many other Syrians, Martini’s family has had to deal with the terrifying prospect of being kidnapped by Bashar al-Assad’s hired thugs, known as shabiha. The paramilitary group has inspired fear in the hearts of Syrians by snatching Assad’s political opponents away from their homes at night. Often, these people never return. Even those who make it back are rarely the same. “The shabiha apparently wanted to kidnap my dad’s brother and hold him for ransom, [so] my uncle had to leave his family for a while,” Martini said. In addition to worrying about his civilian relatives, Martini also worries about his young cousin, who is currently finishing up his mandatory service in the Syrian military.

Though the Arab Spring protests that started in Yemen in January 2011 led to the overthrow of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, the uprising also hit close to home for sophomore Safa al-Saeedi, who is from Yemen. The uprisings were a source of great emotional unrest and anxiety for al-Saeedi and her family. As a power struggle between rival tribes intensifies, the country’s political future is far from certain.

“I was not able to go [home] in the summer of 2011 because of the instability and the events related to the revolution,” she said. “My family had to move from the capital to a different city seeking a safer and a more stable place. My cousin who is only 20 years old was shot in the protest in Taiz City.” Though international press coverage of protest activity in Taiz has not been as extensive as that of other Arab Spring protests, the city—often referred to as the “heart of Yemen’s revolution”—has been plagued by violence in recent months, even following Saleh’s signing of a transition plan in November of last year.

Although Al-Saeedi supported the protests against Saleh—whom she calls an “arrogant and corrupt dictator”—she worries that the Arab Spring has not yet made any significant gains for the health of Yemeni liberal democracy. “At the moment, I do not think I can say [the situation] is good. I went to Yemen this summer, and I felt miserable of what the situation has gotten into,” she recalled.

On the other hand, there has been a marked lack of protests in the Gaza Strip, making the experience far less stressful for junior Ahmed Alshareef, a Palestinian from the region. Unlike Martini and al-Saeedi, Alshareef’s homeland has not been embroiled in violence as a result of the Arab Spring. Alshareef is confident that the lack of widespread of violence will continue in his homeland—that protests against either Hamas or Israel are unlikely.

“An uprising against Hamas won’t happen because it is the only power in Gaza keeping control,” he said. Because common people are grateful for the social services that Hamas provides, including police forces, health care and welfare, rebellion is unlikely, Alshareef said.

A third intifada against Israel is unlikely, he added.

“Barring extreme circumstances, most Palestinians are looking for peace at this point, including many people I know in Gaza. Don’t get me wrong, small bombings and rocket firings happen almost every day but nothing compared to an intifada,” he said.

Animosity toward Israel may heighten as a result of the Arab Spring. Although it raises the potential for regional conflict, Alshareef noted that enhanced animosity may have the positive side effect of increased unity among Arabs.

“I see a trend that isolates Israel. Most uprisings are by the people, and most Arab citizens are in support of the Palestinian cause,” Alshareef said. “The Arab Spring is uniting Arabs into one mentality.”

The future is more bleak in other parts of the Middle East, however. Martini is concerned that many Americans do not have a comprehensive understanding of what is at stake in the Syrian conflict. Many political analysts have suggested that a repeat of previous incidences of political violence are imminent. “Hama 1982” was a massacre in the city of Hama led by former President Hafez al-Assad, father of the country’s current leader, that resulted in the death of 20,000 Syrians. The 1982 massacre was a reaction to widespread dissent in the country at the time—reminiscent of today’s conflict. According to numerous political analysts, another “Hama” could be only a matter of time if the international community does not intervene.

“I grew up loathing this regime and everything it stood for. I grew up lamenting the fact that the words ‘Hama 1982’ were never mentioned by anyone and that one of the worst massacres in modern history was seldom ever discussed,” Martini said.

A long, drawn-out and bloody civil war in Syria is a very real possibility barring international intervention, Martini speculated. This civil war would be reminiscent of the sectarian violence that shattered Lebanon from 1975 to 1990 but on a much larger scale.

If the rebels prevail, Martini said the outcome could still be terrible, since the Sunni majority may seek recrimination against the Alawite Shi’a minority that currently holds power. This type of retaliation happened in Rwanda in the early 1990s when the Hutus massacred Tutsis after toppling them from power.

“I do think there is the very unfortunate potential for a genocide in Syria should the rebels prevail, and the regime’s existing security apparatus be completely disbanded,” he said.

Al-Saeedi is more hopeful. Despite the killings, violence and terrible flow of sectarian zeal, al-Saeedi believes a peaceful outcome is possible because the vast majority of Arabs want peace—even if those voices aren’t the loudest. “I am a strong believer that peace will prevail in the Arab world at some point in the future, because I believe in my people and in their genuine desire for peace,” she said. “The role that the Arab youth is playing in the Arab Spring is inspiring [and promises] a more stable and peaceful future. This sounds quite optimistic, but it happened in the past, [so] why not in the future?”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.