Two weeks ago in this space, I made the case that the performance of Duke’s basketball team has historically declined as the ACC season progressed. Like a good scientist, I declined to speculate in print about the causes behind that decline.

Of course, I had my hypotheses, and in the two intervening weeks, I’ve been back in the lab (read: on kenpom.com and statsheet.com) working on The Unified Theory of Duke Basketball Performance (At Least Over the Past Six Years Or So).

I took as my starting point one of the most common criticisms of Duke head coach Mike Krzyzewski, and one that is particularly relevant this year: He plays his star players too many minutes, causing them to tire and collapse down the stretch. Defenders of this theory have ample anecdotal evidence to back up their point—most recently, J.J. Redick’s perceived slump to end the season in 2006 and Kyle Singler’s decline last year. And with Singler, Jon Scheyer and Nolan Smith each averaging more than 35 minutes per game this season, it’s a pressing concern.

So I looked at the last nine years, and divided all the Blue Devil starters into two groups—high-minute players and low-minute players. High-minute players were defined as guards that averaged 34 minutes per game or more over the course of the season and forwards that averaged 32 minutes or more. Over the past nine years, 12 individual seasons have met this definition: Shane Battier (2001), Mike Dunleavy (2002), Chris Duhon (2002-2004), Daniel Ewing (2005), Redick (2005-2006), Shelden Williams (2005-2006), Josh McRoberts (2007) and Singler (2009).

To measure performance, I used individual offensive rating, a tempo-free tool that essentially measures how many points a player individually creates per 100 possessions. Field goals, free throws and offensive rebounds are point-creating events; turnovers and missed shots go down as wasted possessions.

When I graphed individual offensive rating over the course of the ACC season for high-minute and low-minute players, I found a surprising result. High-minute players did not experience a significant decline in offensive performance over the course of the season. Low-minute players actually did have a slight decline, but for both groups, the date explained less than two percent of the decline in individual offensive performance. Furthermore, no single high-minute player experienced a significant decline or rise in offensive performance over the course of the year.

At this point, I was at a loss. If Duke was declining over the course of the season, but none of the individual players showed any signs of decline, then how could it be happening?

Then, quick as a Brian Zoubek hook shot, it hit me. It’s the defense, stupid!

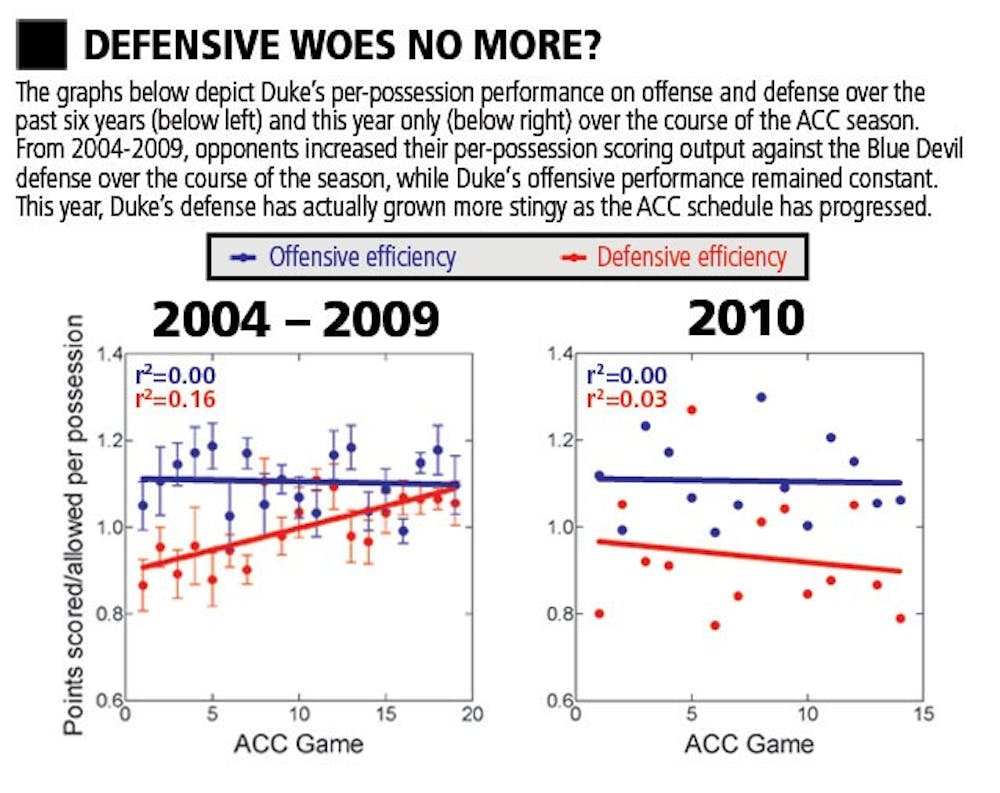

I repeated my scatterplots from two weeks ago, comparing efficiency to progression through the ACC schedule, except this time, instead of subtracting defensive efficiency from offensive efficiency to arrive at efficiency margin, I kept the two factors separate.

Not surprisingly, given the stability of individual offensive players’ performance over the past six years, offensive efficiency remained constant over the course of the season. However, Duke’s defense allowed 0.01 more points per possession every game. And that difference adds up. Assuming 67-possession games (the national average), Duke’s defense has historically yielded nearly 13 more points per game in the last game of the conference season than the first (0.01 x 67 x 19 = 12.7).

I now knew that Duke’s late-season slides could be almost wholly attributed to a decline in defensive performance; still, I was no closer to determining whether this decline was due to fatigue or some other factor.

Unfortunately, there’s no statistical magic bullet for measuring fatigue. So instead I got to thinking: When I play basketball, what sorts of defensive things do I stop doing as well once I get tired? I don’t box out, don’t get in passing lanes to steal the ball, don’t challenge shots as effectively and I reach in rather than moving my feet on defense.

Fortunately, these are things that one can measure statistically, by looking at the percentage of an opponents’ missed shots that a team rebounds (defensive rebound percentage), the percentage of opponents’ possessions that end in steals (steal percentage), the percentage of opponents’ shots that are blocked (block percentage), and the frequency with which an opponent gets to the free throw line (free throw rate). You could argue that the percentage of shots an opponent makes could also be tied to fatigue—in that an opponent will have more uncontested and lightly contested shots— but this could also be due to a number of other factors, most prominently, better offensive execution.

I ran more spreadsheets, this time comparing defensive rebound percentage, steal percentage, block percentage and free throw rate to time point in the ACC schedule over the last six years. Of all four “fatigue-related” statistics, only steal percentage showed a significant decline—Duke stole the ball less often as the season went on. Defensive rebound percentage, block percentage and free throw rate were essentially constant.

Still, that significant decline in steal percentage was intriguing, especially given its obvious tie-in with fatigue. I looked further into the data, and found that opponents’ effective field goal percentage (same as field goal percentage, but a made three-pointer counts for 1.5 points) also increased significantly over the course of the season.

Of course, the problem with effective field goal percentage is that there’s no true way to know whether an opponent made more shots as a result of lax defense or better offensive execution.

However, I reasoned that opponents’ assist rate (percentage of baskets that are assisted) could provide a clue: Better offensive execution is (generally) characterized by better passing. And when I crunched the numbers, I found no significant increase in Duke’s opponents’ assist percentage over the course of the season.

Objectively speaking, the decline in Duke’s defensive performance over the course of the ACC season can be attributed only to a decline in steals and improved shooting by opponents. Tellingly, opponents are not passing the ball better, only shooting better, making improved offensive execution by the opposition an unlikely cause of Duke’s late-season defensive woes.

The combination of data paints a picture of a team worn out on defense late in the year, unable to athletically contest shots or steal away passes. Of course, a team can tire for many reasons, either for lack of depth, a coach’s insistence on playing star players for too many minutes or overly rigorous practices. This analysis is incapable of differentiating between those causes.

Still, while it’s too early to draw any conclusions from this season, Duke’s defensive efficiency has actually improved so far, and its steal percentage and effective field goal percentage allowed have remained close to constant. So far, keeping Scheyer, Singler and Smith on the court hasn’t hurt the Blue Devils at all.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.