Once upon a time—or a couple weeks ago—Duke had one of the most efficient rushing defenses in football.

And just as quickly as the stout unit materialized, it’s disappeared.

After getting shredded by Florida State’s physical backs and Pittsburgh’s motion offense, the cratering Blue Devils have fallen from No. 7 in rush defense in the country to No. 40. On a four-game losing streak, Duke’s failures have been all over the place, from allowing explosive plays to strong power runs on first and second down, leaving the coaching staff without one specific area to focus on.

“There was no one real big theme,” Blue Devil head coach David Cutcliffe said on his weekly teleconference. “We didn’t play as well against the run as we have been. It’s a multitude of things. It wasn’t so much tackling as it was fitting in the right gaps. Just some mistakes that we don’t usually make. You have to give Pittsburgh credit for some of their shifts and motions and movements.”

One play seemed to epitomize Duke’s failings—running back Darrin Hill’s 79-yard touchdown that nearly matched his season rushing total. On a run up the middle, Hill was able to streak all the way to the end zone without a Blue Devil ever laying a finger on him.

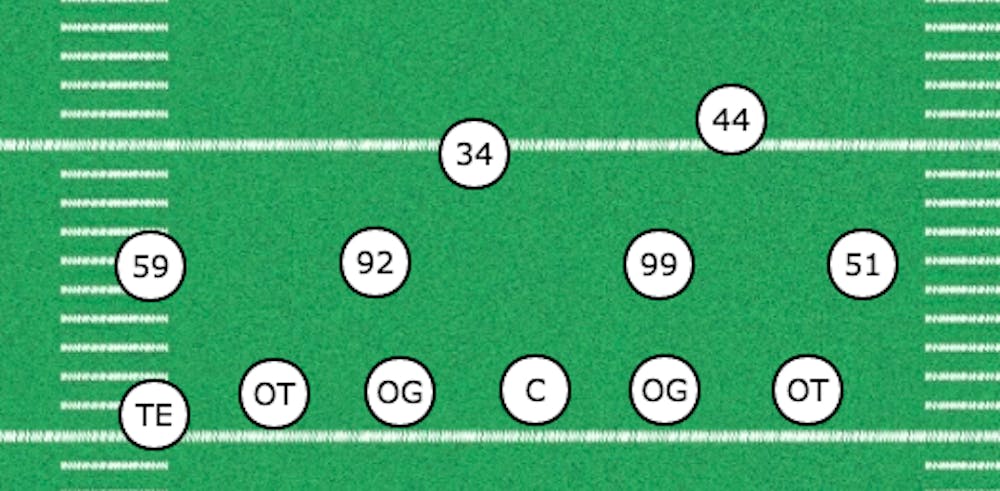

So with six defenders in the box lined up against five offensive lineman, how in the world could that happen?

It’s simple—Duke forgot to mind the gaps.

Full-speed, it’s hard to see exactly how that happened, but it’s clear that the hole was far too big for Duke to have any chance to stop Hill.

“[It] was a misfit—there was a gap that was there,’ Cutcliffe said. “There are reasons that it can happen, and it happened. It’s a combination of players. It’s not any one thing.”

So what does Cutcliffe mean by all that?

A basic fundamental of defensive football is stuffing gaps between offensive linemen that are standing next to each other.

Thus, assuming the tight end splits down the sideline in this formation below, No. 59 (Tre Hornbuckle) would want to fill up the gap off the left offensive tackle’s shoulder, No. 92 (Edgar Cerenord) would want to fill up the gap to the tackle and the guard, and No. 34 (Ben Humphreys) would plug the gap between the guard and the center, and so on and so forth.

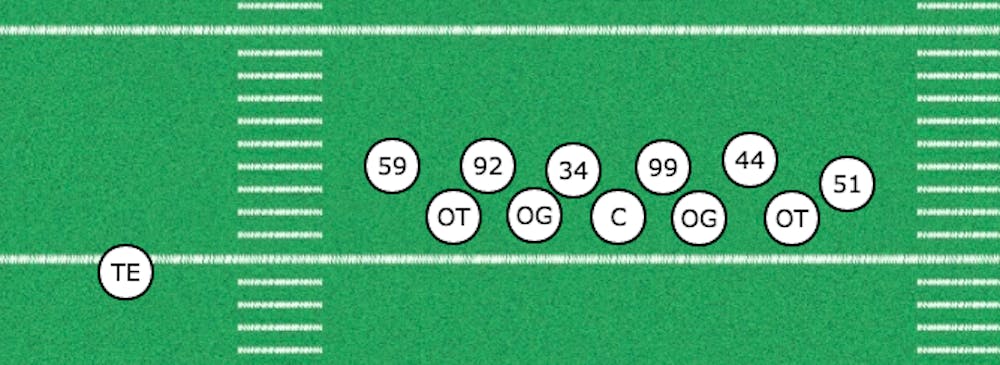

POST-SNAP BELOW

Ideally, after all of that, Duke would have six defenders on the line, plugging every hole between the offensive linemen. They wouldn’t have to break through to the backfield necessarily—just hold their ground enough to pounce on Hill as he tries to squeeze through the line.

But that didn’t happen—or anything close to it. As Cutcliffe said, it was a team failure that was emblematic of their struggles the past two weeks.

Pittsburgh set its tight end in motion—in this case by formation only, as it was actually running back Qadree Ollison lining up where a tight end would—which seemed to confuse Hornbuckle, who was slow to rush forward. The motion also sent safety Alonzo Saxton II chasing Ollison away from the hole cleared for Hill—he would have been there to make the tackle in space otherwise.

The rest of the defensive front six didn’t seem to follow its assignments and ended up in suboptimal position—Cernord and Humphreys got bunched up with Hornbuckle, putting three defenders on two linemen, which would normally be an advantage.

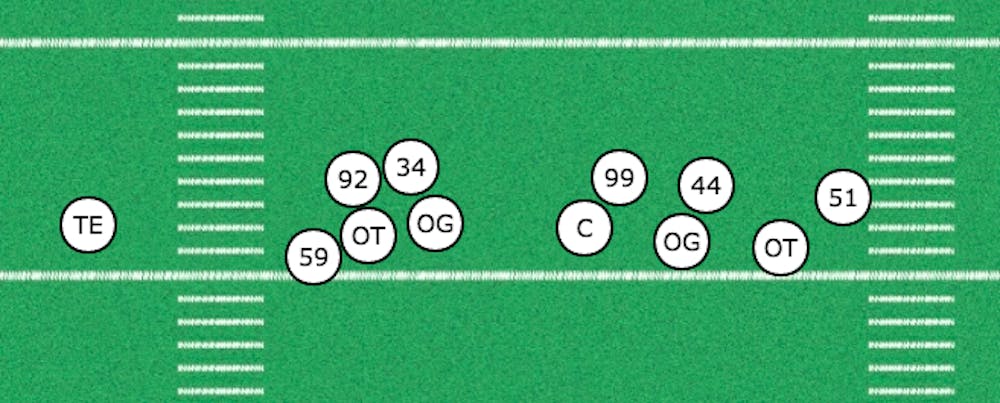

But because Humphreys was pushed away from the hole, he couldn’t cover the gap between the guard and center—as was the case for No. 99 Mike Ramsay, below.

This wasn’t just coach speak—the Blue Devils truly failed as a team on this play, not just one individual player missing an assignment.

“The run game is all going to fall initially on linebackers and defensive front people,” Cutcliffe said. “When it gets beyond them, and certain mechanics have to happen for the safety to be able to fit properly. If that doesn’t happen, your safety might not be in the same alignment that he would need to be in. They do a lot of motion that challenges that, but it didn’t end up just being that.”

Cutcliffe said it was the same situation on Hill’s later explosive run, which went for a 92-yard touchdown that thrust the Panthers back in the game, cutting the lead to 17-14 at the end of the third quarter. But it wasn’t just the big plays that crumbled Duke’s front.

“Quite honestly, it wasn’t just those two home runs,” Cutcliffe said. “There were too many six-yard runs, based upon the same thing.’

The Blue Devils’ defensive execution woes were palpable throughout—excluding HIll’s two big touchdown runs, they yielded a clean 4.0 yards per carry to Pittsburgh’s running backs. This consistency wore down Duke, allowing the Panthers to hold the ball for nearly two thirds of the game despite scoring 14 of its 24 points in two one-play drives that lasted a combined 24 seconds.

“It’s a conglomerate of things playing defensive football against a good run team,” Cutcliffe said. “If you don’t do it, you’re going to get burned, and unfortunately, we did.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Managing Editor 2018-19, 2019-2020 Features & Investigations Editor

A member of the class of 2020 hailing from San Mateo, Calif., Ben is The Chronicle's Towerview Editor and Investigations Editor. Outside of the Chronicle, he is a public policy major working towards a journalism certificate, has interned at the Tampa Bay Times and NBC News and frequents Pitchforks.