On the first floor of the Friedl Building at Jameson Gallery is an exhibit whose two wooden doors at the entrance open for everyone. Launched Aug. 28, the “Be Patient | Se Paciente” exhibit displays the works of Dr. Libia Posada, a surgeon and contemporary artist from Medellín, Colombia.

A year ago, Duke’s Franklin Humanities Institute started the Health Humanities Lab as a part of efforts to promote interdisciplinary collaboration among health, arts and humanities. The works of Posada stood out as one of the perfect examples of connecting all three disciplines.

“[We were] looking for possible people to come and give us more content from dimensions of art, health and medicine, to work with us,” Curator Miguel Rojas-Sotelo said. “Dr. Posada was, of course, on the top of the list.”

Rafael Osuba, founder and artistic director of the Artist Studio Project—which provides spaces for primarily Latinx artists in North Carolina to promote their skills and works—produced the exhibit. The Katz Family Foundation, managed by the Kenan Institute of Ethics, provided the grant to invite Posada as a Katz family fellow and the place to display her works.

The exhibit is notable for its title, which can be understood in two different ways. Because of the double meaning of the word “to be” in Spanish, “Se Paciente” can be interpreted both as an order—“Please be patient”—and as the state of being patient.

“To be patient means to have time, to understand, to think and to live,” Posada said.

To understand the combination of art and medicine, one of the main themes of the exhibit, it is important to understand the conception of medical practice in Colombia. In many Latin American countries, medicine is linked more with the solution of social problems, such as poverty and displacement due to conflicts, than with business.

“One of the topics of Dr. Posada’s works is problematizing the issue of medicine as an industrial complex, in which the patient becomes the client,” Rojas-Sotelo said. “A medical doctor is also a social scientist.”

As an example, in Colombia, physicians-in-training have to work one year for free during their training to serve their communities and understand social problems.

Coming from a school where social medicine was in the center of training, Posada tries to connect the historical, political, and social concerns of both art and medicine.

“People go to hospital or [other] medical spaces to look for cure, but their bodies are talking to us about social problems, more than personal problems,” Posada said through a translator.

She said she became an artist, as well as a surgeon, because she was interested in how to define human beings, herself and the world in order to understand life. To her, human beings and their experiences are at the center of both art and medicine.

Posada’s thoughts about her gender identity have also influenced her works as an artist.

“I have a female body,” Posada said. “[But] I [primarily] think of myself as a human being.”

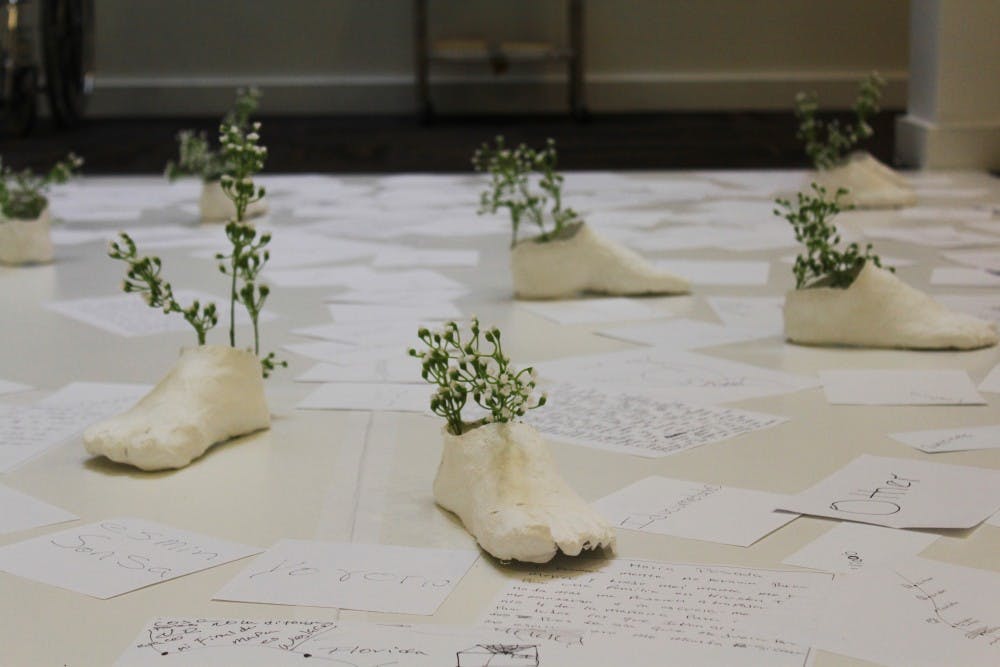

Although she does not consciously think of her art and practice as a surgeon from a woman’s perspective, her experiences as a woman are reflected in her works. One of the works in the exhibit shows the feet of Latin American immigrant women who had to flee from wars and conflicts in their countries in order to save their children and themselves because their men were already dead or had become part of the conflicts. Through the work, Posada portrays the histories of families, towns and communities reflected in the women’s feet.

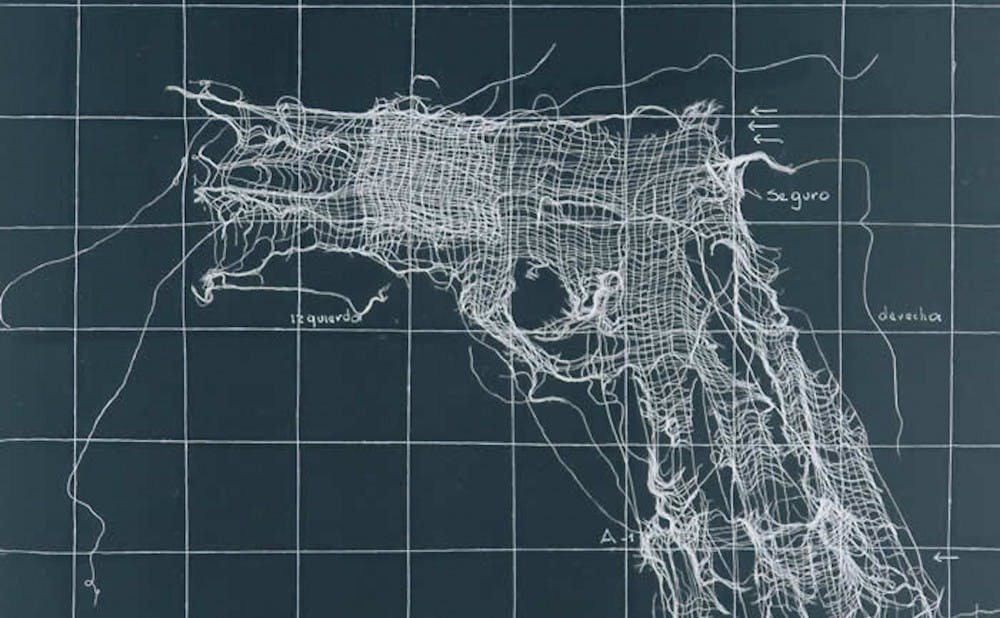

Many of the works in the exhibit are centered on the color white. Through materials used to cure illnesses and scars such as gauze and gesso, Posada brings the viewers’ attention to the problems that are covered by those perfect white surfaces. Her works look clean, beautiful and harmless from the outside, but under the beautiful surface are ugly social problems that have been affecting so many people.

“What makes Dr. Posada’s work very interesting and impactful is that she uses the materials you would find in trauma centers to depict different types of trauma,” Osuba said.

The types of trauma range from the scars that are left behind due to displacement to those left by domestic violence. The exhibit encourages visitors to have discussions about problems that people often choose not to talk openly about.

“Some people [are] only going to be able to see what is on the wall,” Osuba said. “Others are going to come here and are going to see what is in [immigrants’] souls and the struggles they had to go through.”

Editor's note: Some of Dr. Posada’s quotes were translated from Spanish to English by Rojas-Sotelo and Osuba.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.