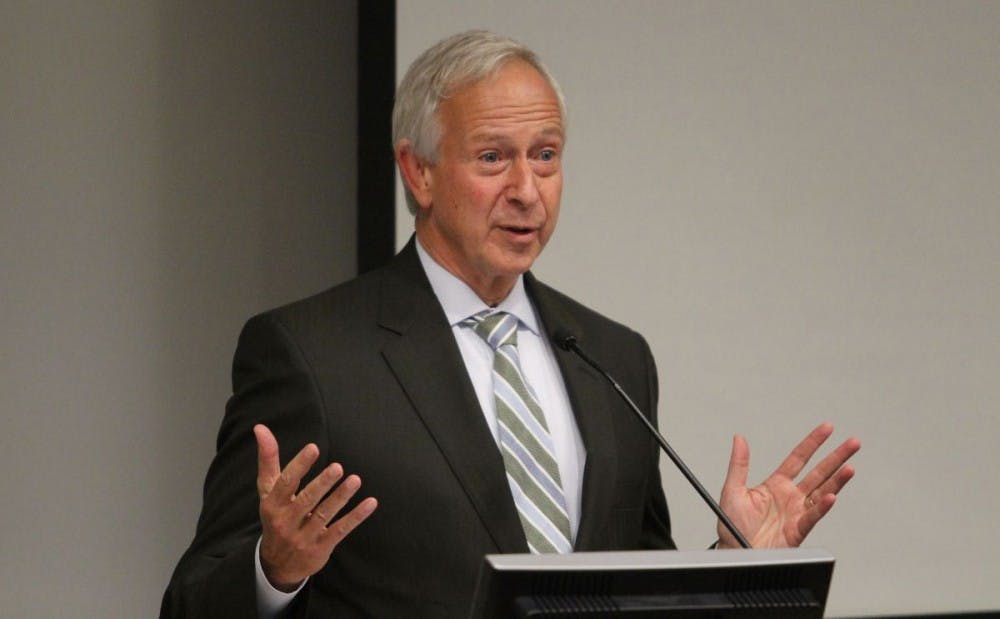

When President Richard Brodhead arrived on Duke’s campus in 2004, the Nasher Museum of Art was still a construction site.

Walking around its grounds with the museum’s namesake Raymond Nasher, Brodhead was struck by the opportunity that came with the youth of his new university. He had arrived in Durham following a 32-year career at Yale University. Yale, one of the oldest colleges in the country, had an art museum dating back to 1832—six years before Duke was even founded.

When Brodhead took the job at Duke, he knew he wanted a school with different opportunities than those at Yale. He viewed Duke’s youth as part of its potential. The Nasher was just one example of it.

“They had just put up the steel supports that would frame the incredible skyline,” Brodhead remembers. “We’re at the moment of innovation, the moment of creativity. And to be here and to have that happening here and to get to watch the growth of the arts at Duke at that time, it was thrilling for me.”

See our other Brodhead coverage:

In the eye of the storm: The trials of President Richard Brodhead

Since that day, the pace of change at Duke has not slowed—if anything, it’s sped up—leaving the University a demonstrably different one than what Brodhead found when he arrived 13 years ago.

Duke offers an increasingly diverse student body more financial aid than ever before. Physically, West Campus has transformed. Durham has been revitalized, as has Duke’s relationship with the city. Duke Kunshan University is open, its undergraduate curriculum approved. More than 3,600 students have volunteered more than one million hours through DukeEngage.

Sitting in his office in the Allen Building with a Diet Dr. Pepper at his side, Brodhead reflects on those changes, as well as the University’s future. He speaks with rhetorical flourishes learned over decades spent as an English literature student and professorcombined with the practiced diplomacy of a university administrator.

When he thinks about the timing of his presidency, Brodhead says he realized there are some projects that fit well with his last year—including the conclusions of the Duke Forward Campaign and construction on West Campus. He also says he’s not worried about the projects that he won’t be able to see finished.

“It’s really not the nature of the kind of job I have,” he says. “A university is always being created, in every dimension.”

Brodhead’s biggest priority

Brodhead initially demurs when asked about his largest accomplishment —“it isn’t the nature of my work that you think of it that way”—but then quickly settles on his response.

“For the artifice of the interview, I’ll give you my answer—financial aid,” he says. “I’m not a boastful person, but I think I can say I’ve helped this University understand that this is not a cause among others, it is the cause that underlies and enables others.”

In the final fundraising campaign before Brodhead took office, the University did not mention a financial aid goal. When Brodhead arrived, he made it a priority. The first major project launched by Brodhead, called the Financial Aid Initiative, raised $300 million.

Over the course of his tenure, Brodhead has raised more than $750 million for financial aid. Much of that came from Duke Forward, the university’s largest ever capital campaign, which successfully reached its goal of $3.25 billion in July, almost a year ahead of schedule.

For the Class of 2020, the University also launched the Washington Duke Scholars program, designed to support first-generation students. Brodhead says his proudest accomplishment isn’t “the dollars,” but the Duke community’s understanding that financial aid is an issue “of the utmost importance.”

When Brodhead arrived, about 40 percent of Duke undergraduates received financial aid. Today, more than 50 percent of Duke undergraduates receive aid.

A study released in January showed that despite progress made, the wealth gap continues to pose an obvious challenge for Duke and many of its peer institutions. At 38 colleges in the U.S.—including Duke and five schools in the Ivy League—more students came from the top one percent of the income scale than from the bottom 60 percent. At Duke, 19.2 percent of students come from the top one percent, defined as families who make more than $630,000 per year, and 16.5 percent of students come from the bottom 60 percent, defined as families who make less than $65,000 per year.

Brodhead, who says he had read the study with interest, notes that he was saddened but not surprised by its results. He calls the wealth gap and the correlation between low income and poor educational preparation the “the single thing that has been most dismaying in my academic life.”

“The real trick of it is to get people to realize they could aspire to go to Duke who don’t know anybody who ever went to Duke, who don’t know anyone who tells them they could get in there, who don’t know anything about the mechanisms of financial aid,” Brodhead says.

The problem, he adds, is that income inequality and the unequal access to education that comes with it are not problems that can be quickly or easily solved.

“This is a problem that you always have to keep working at, because the tide is flowing in the wrong direction,” he says.

The overhaul of West Campus

The physical alterations to campus that have taken place under Brodhead’s leadership are the most obvious changes to the University since he arrived.

For much of his tenure, cranes dotted Duke’s skyline, sometimes leading to complaints from students and Durham residents. Although it continues on East Campus, construction on West Campus has largely drawn to a close — leaving West a newer and brighter space than it once was.

Before the financial crash in 2008, Duke had plans to build a major residential space at the corner of Anderson and Campus Drive. But when the market crashed, that “become completely nonviable,” Brodhead says.

“After the collapse, I think we looked at the West Campus and we said, ‘Wouldn’t something be wrong if you built a gorgeous, new residential campus and the core of the campus is in as bad of shape as West would appear,’” Brodhead says.

With a gift from the Duke Endowment in Charlotte and a donation from David Rubenstein, the chair of the Board of Trustees, the University renovated Baldwin and Page Auditoriums and rebuilt West Union and what became Rubenstein Library. Rubenstein, Trinity ’70, was elected to become a member of the Harvard Corporation and will step down from Duke’s Board on July 1.

Those changes weren’t just about improving Duke’s physical appearance, Brodhead emphasizes. He says that in the wake of the lacrosse case, the University recognized the priority of creating of communal social spaces on campus that were not associated with sports teams or Greek life.

“The complaint about fraternities was that they alone owned space, that it was this organizing feature of social life that some groups owned space, and that there was very little space for anyone else to do anything in,” Brodhead says. “So we have really made quite a concerted effort on this campus to give priority to the creation of unowned, completely shared community space.”

Examples he cites include the renovation of Marketplace on East Campus, the common space under Gilbert-Addoms dormitory, West Union, the Edge and the Link in the library.

The biggest priorities for the University going forward, Brodhead says, are gathering the funding to renovate engineering buildings and focusing on student housing “after Central Campus leaves this world.” But he doesn’t think the University will see “anything in the next five years like what we saw in the last five years” in terms of the scope of construction.

A changed culture?

Brodhead says that it is not just the physical landscape of Duke that has changed since he arrived in Durham.

If a student at Duke in 2003 “went into a deep sleep” and woke up on today’s campus, they would find it a very different environment than the one they were familiar with, Brodhead suggests. There are more ways to engage outside of the classroom—and there is more willingness to do so.

DukeEngage, the immersive summer service program launched in the summer of 2007, and Bass Connections, the interdisciplinary research initiative created in 2013, are two examples Brodhead cites as opportunities Duke students have to engage outside of a traditional classroom setting. Ten years ago, Brodhead adds, 15 percent of students did an independent research project. Today, that number is roughly 50 percent.

“Duke students were always as smart as the best students anywhere, but they didn’t always think of themselves that way,” Brodhead says. “And I would say I think there was a time when it used to be less cool to be smart than it is now.”

In 2004, the University admitted 22 percent of its applicants. For the Class of 2021, 9.2 percent of applicants were accepted.

Another part of the social change on campus can be attributed to decisions made by the University. In 2010, for example, Brodhead’s administration opted to permanently end Tailgate after a 14-year-old sibling of a Duke student was found passed out in a porta-potty.

"The 14-year-old hadn’t just passed out,” Brodhead told The Chronicle in 2013. “The 14-year-old had been left in an outhouse passed out by a sibling who had gone on without even knowing it. That sibling didn’t deserve for the sibling to still be alive."

Brodhead, who told The Chronicle in 2013 that he had never attended tailgate, said “you couldn’t have the good part of it if it would always degenerate into the horrible dangerous part of it.”

In the years since it was shut down, several groups, including Duke Student Government, have tried recreate the tailgating tradition, but no comparable tradition has emerged to replace it.

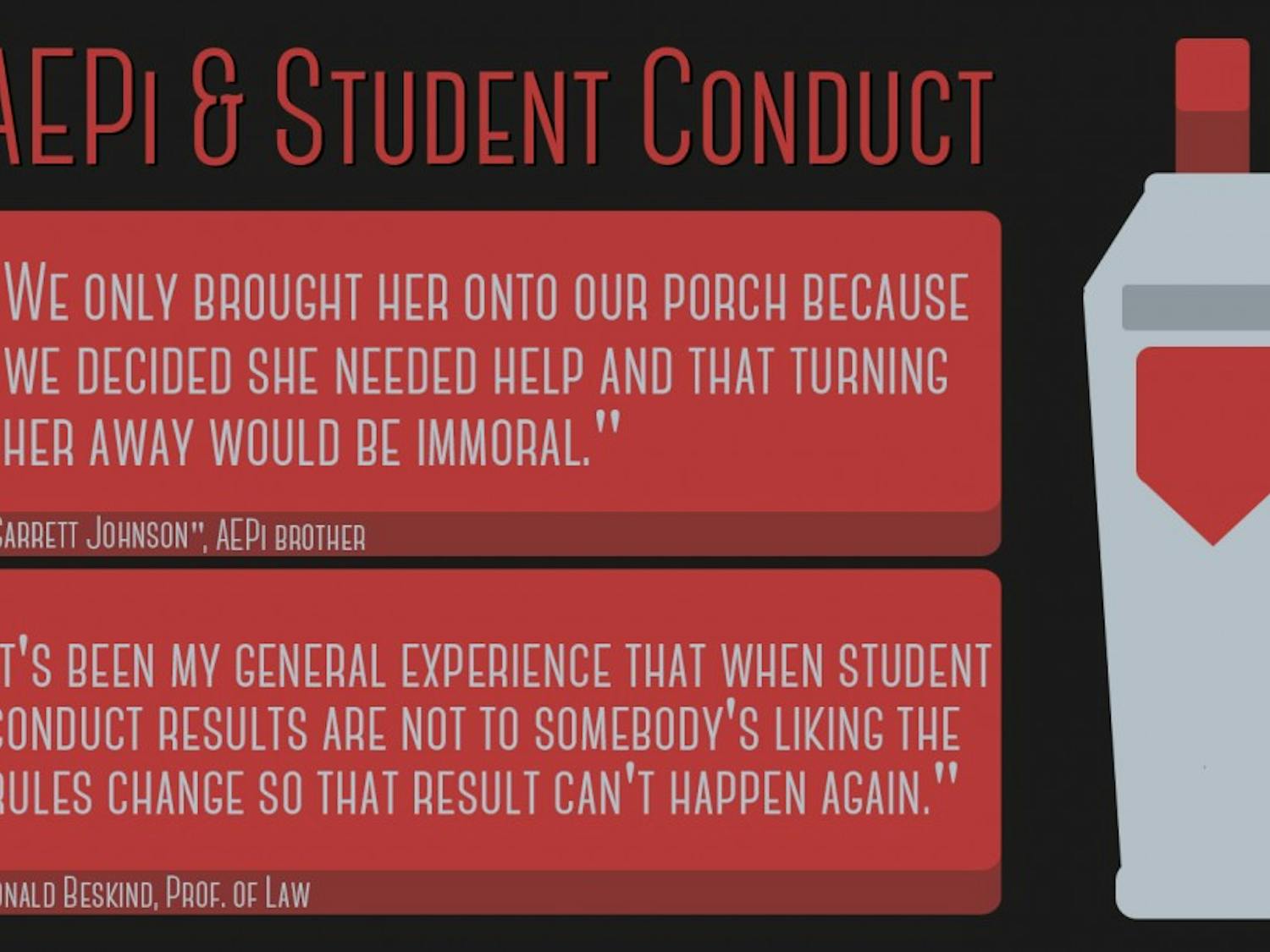

Duke’s emphasis on Greek life has also changed during Brodhead’s time at Duke—with more selective living groups and independent houses lining the quads where fraternities once dominated.

After the lacrosse incident, a special University committee published a report suggesting that Duke should abolish the Greek system entirely. But the report—which Brodhead called “a blunt instrument”—didn’t explain what would happen to the historically African-American sororities and fraternities or how SLGs would be affected.

“We came to understand student have some freedom to affiliate as they choose, but what we wanted was to reach a better equilibrium of the perks for Greek life and the perks for everyone else,” Brodhead says.

A big part of that was creating shared public spaces and making sure that the housing model allowed independent students to form the same sense of community that students affiliated with Greek life or SLGs formed.

Duke and Durham

As the lacrosse case unfolded in 2006, the national spotlight was placed on Duke’s relationship with Durham.

The New York Times declared,“New Strain on Duke’s Ties with Durham,” and ESPN went with, “Turbulent Times for Duke and Durham.”

But Thomas Ferraro, Frances Hill Fox professor of English, says that although media coverage from the lacrosse case often focuses on the negative aspects of the Duke-Durham relationship, the work Duke has done in downtown Durham has been “very impressive.”

Duke, he notes, leases more than one million square feet of office space in Durham, which it rents from businesses that pay taxes that go back to the city. Because of its nonprofit status, Duke would not have to pay taxes if it owned the space.

“It costs us however much more a year, but look at what has happened to Durham,” Ferraro says. “Yale bought the buildings. Yale was trying to build a fortress. We were trying to open up the corridors. We have dedicated bus systems that take people not only to [the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill], they take them downtown.”

The University and Duke University Health System have also contributed to the downtown revitalization by developing historic buildings, investing in local economic partners and locating 2,000 employees in almost 528,000 square feet of office space downtown.

Following the lacrosse case, Brodhead created the position of vice president for Durham and regional affairs and appointed Phail Wynn to fill it. Wynn immediately began conducting meetings with local government officials, community stakeholders, business leaders and neighborhoods to find ways to better engage Duke and Durham.

DKU and Duke’s impact abroad

Brodhead’s commitment to being a good neighbor extends beyond Durham. The day after commencement, he will get on a plane to China.

The tight turnaround, Brodhead says, is “a bit much” for him. But an advisory board for DKU is meeting, and Kunshan has a major conference taking place where Brodhead was told his “being visible would be much appreciated.”

It will be one of many trips to China that Brodhead has made as DKU has gotten off the ground. When The Chronicle spoke with Brodhead in March, he had just returned from a four-day trip to the University—which he said convinced him that progress was going well.

“Duke used to not be very well-known in China,” Brodhead says. “When I was first president, people who were very well educated knew about Duke, but they didn’t know much about it. Now Duke is very, very well-known in China.”

That matters, Brodhead says, because China “is the great fact of the next 30 or 40 years.” When seen in light of this, launching a four-year degree program at DKU is challenging but eminently worthwhile, he says.

“A university that has found a way to engage [China] will be in a much stronger position, even for its students on this campus, than a school which hasn’t found a way to engage it,” he says.

But DKU had its share of stops and starts, including issues with construction and funding that contributed to a three-year delay in its opening in Fall 2014. Last December, the Board of Trustees approved the establishment of a four-year undergraduate liberal arts degree at DKU—meaning that those who graduate will receive a Duke diploma with a notation that says it was conferred at DKU.

DKU is just one example of what Brodhead says was the forward-thinking innovation he knew he would find at Duke. He says the “balance of tradition and innovation” is set very differently at Duke than it was at Yale.

“This place is so open to experimentation, innovation,” he says. “And so I thought, ‘that’ll be a fun place to be a president. At a place that’s not all about trying to keep things more or less how they are.’”