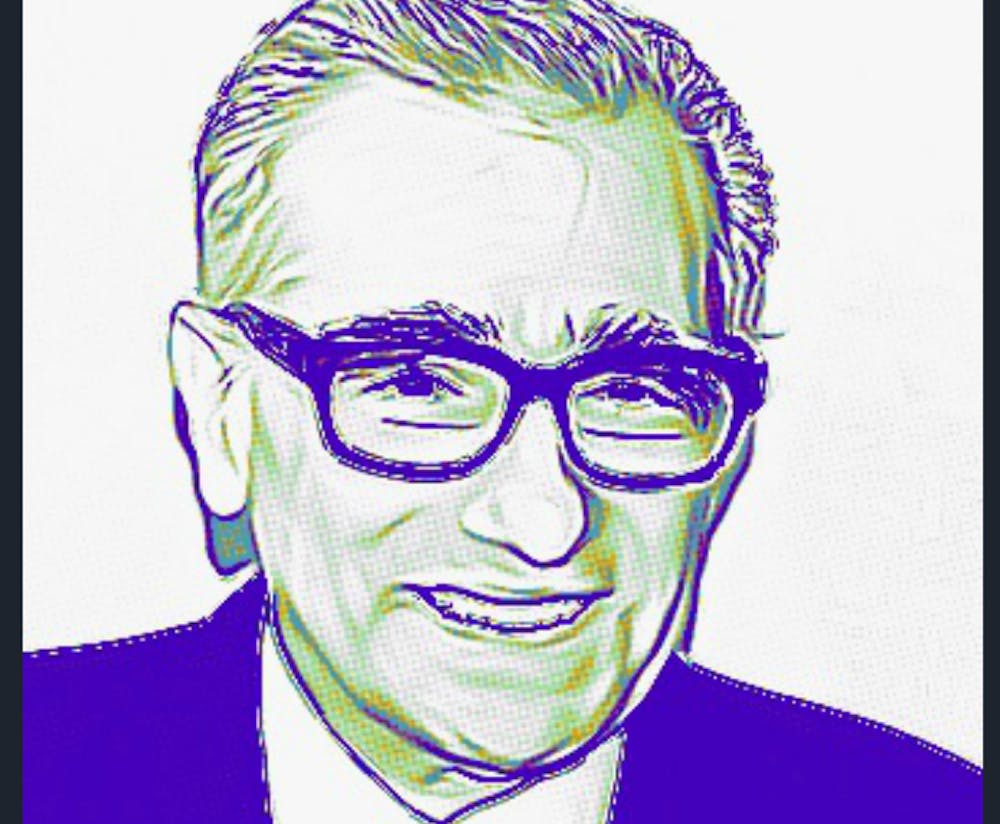

Martin Scorsese isn’t the kind of director whose repertoire of films beckons the label ‘religious.’ Considering his most popular works are character studies of morally bankrupted and deeply flawed men (“Taxi Driver,” “Goodfellas” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” come to mind), it must strike the casual film-watcher as odd that “Silence,” Scorsese’s most recent film, is a veneration of Christianity and its practices. But Scorsese, a lapsed Roman Catholic who aspired to priesthood in his adolescence, has always held a deep affinity for religion, and “Silence” is his homage to the predecessors of his faith.

“Silence,” adapted from a 1966 novel of the same name by Shūsaku Endō, follows two 17th-century Jesuit priests, Father Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Garupe (Adam Driver) of Portugal, as they traverse through feudal Japan to locate their missing mentor, Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson). Endowed solely with the knowledge that Ferreira has renounced his faith after repeated subjections to torture by the Japanese government, Rodrigues and Garupe are propelled by their own disbelief at Ferreira’s situation to seek answers for his apostasy. Guiding the two Jesuits through the foreign terrain is Kichijiro (Yosuke Kubozuka), a Japanese fisherman who lost his family to the anti-Christian massacres performed by the government.

When Rodrigues and Garupe arrive in a small village called Tomogi, they witness firsthand the oppressive nature of the Tokugawa shogunate. Christianity, brought to Japan in 1549 by Catholic priests, has been outlawed, its adherents violently and dogmatically persecuted. As such, the Japanese Christians must practice their faith in secret, prayers whispered surreptitiously and crosses carefully tucked away. It is an unbearable burden wrought onto the shoulders of the Japanese Christians and Rodrigues struggles to understand how God could allow their existence to be spent in silent suffering.

Scorsese’s camera captures sweeping birds-eye shots of the Japanese thickets and wide angles of the swelling, foamy sea, the persistence of God’s gaze upon his own handiwork obvious. The no-nonsense direction is reminiscent of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa and an ostensible departure from Scorsese’s previous works–lengthy Steadicam shots and fast-paced editing have no place in such a vast, dark tale of spirituality. Perhaps this is why Rodrigues’s insistence that Christianity can take root in the “swamp of Japan” falls flat when juxtaposed with Scorsese’s forceful depiction of nature in “Silence.” What place does the Christian God have in a country where the sea is an unrelenting threat and the soil’s ability to yield crops is unreliable? To place one’s faith in anything but the tangible is wearying and difficult, and the missionaries’ determination to ascertain Christianity as more important than survival is selfish at best.

“Silence” chiefly uses Father Rodrigues as a proxy for these questions of faith which have certainly plagued humans since the dawn of our consciousness of God. Why are certain lives spent in torment while others remain largely untouched by strife? Is an outward abandonment of faith for the sake of self-perseverance an unforgivable sin or is martyrdom the worst crime a Christian can commit? The lack of communication between God and Rodrigues fuels the latter’s mounting disillusionment with his faith, Rodrigues musing that he is perhaps “praying to silence” instead of a benevolent being. Still, though, he can’t help but compare his plight to that of the Jesus–to Rodrigues, the trials of faith and persecution that he endures are not dissimilar to the tribulations that God’s son had to withstand.

It’s in this internal struggle of godliness that Rodrigues becomes a recognizable Scorsese character, perhaps to a fault. As his purpose in Japan loses its clarity and his moral compass skews further, the priest’s attempts to push Christianity feel desperate and forced. The Japanese Inquisitor (Issey Ogata), whose job is to rid Japan of Christianity, is an arguably more interesting and persuasive character than the weak-willed Rodrigues. The Inquisitor doesn’t hesitate to accuse Rodrigues of egotistically trying to exemplify Jesus, pointing out that the price for his glory in serving God is the suffering of the Japanese Christians. As long as he holds fast to his faith and refuses to renounce the church in pursuit of converts, the Japanese Christians will continue to be slaughtered in hordes.

The film, which sprawls over an indulgent two-hour and 40-minute runtime, agonizes over the purpose of religion and the absence of God in his most-needed moments, painting a difficult but often lackluster portrait of spirituality. More questions are posed by “Silence” than answered, but it’s feasible that the complex existence of faith has more room for discourse than sweeping resolutions. Still, “Silence” is Scorsese’s lovingly imperfect homage to the faith that shaped him, a passion project that never claims to be anything more.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.