Many Durham neighborhoods have experienced a surge in development in recent years, bringing new residents and increased costs.

Gentrification in Durham was the topic of discussion Wednesday night at a presentation by Melissa Norton, the project coordinator of the Durham Living Wage Project. The talk at the Franklin Humanities Institute Garage aimed to start a conversation among community members and address the problem of long-time and often lower-income Durham residents being displaced by an increasing number of wealthy, white residents.

“As I talk to people about gentrification, I come up against hopelessness and cynicism, and I hear that and it’s real, but it also doesn’t promote action,” Norton said. “There are things we can do to fight for an inclusive central city.”

Robin Kirk, co-director of the Duke Human Rights Center, introduced the topic of the evening and urged the community to view gentrification as a human rights concern.

“There is something deeply unfair happening in Durham right now and we wanted to try and get a handle on it and use this idea of human rights to do that,” Kirk said, citing Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of property. “The change in Durham has been dramatic and very fast. Very little has been done to include affordable housing.”

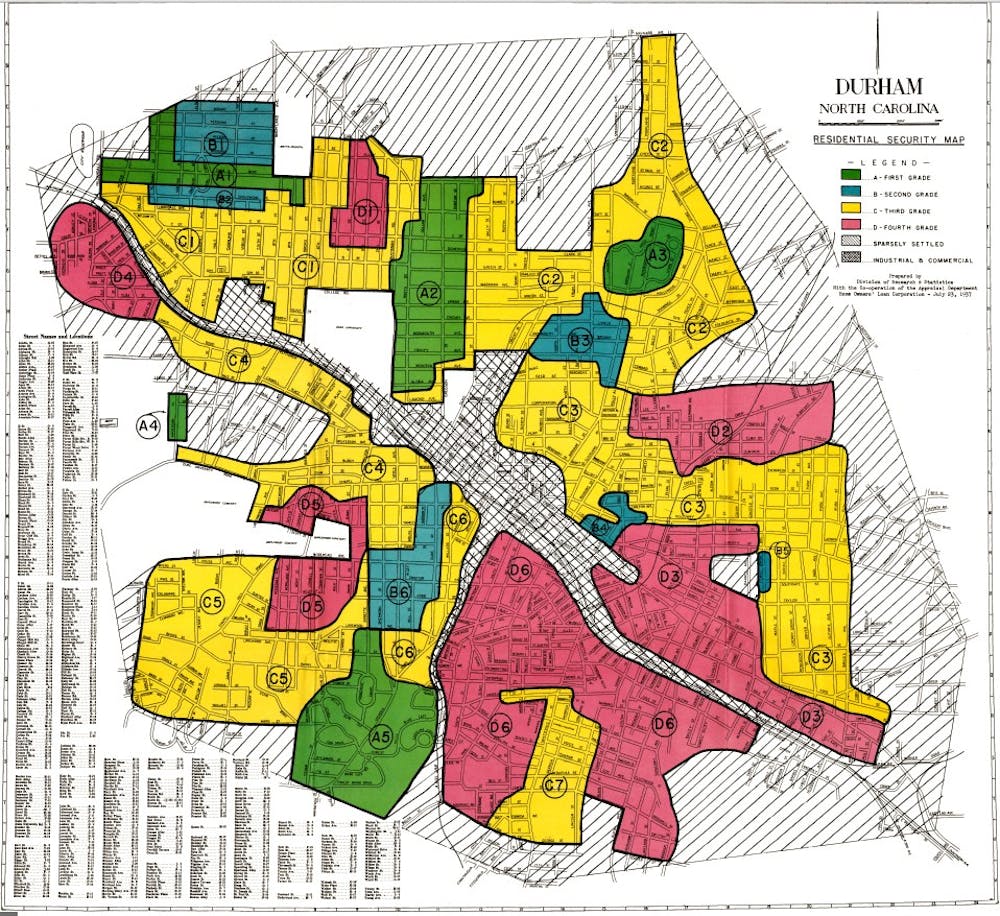

Norton emphasized that historical forces set up the gentrification process in Durham. She pointed to practices of structural racism such as redlining, a process started in the 1930s by the federal government that marked predominantly black neighborhoods as risky investments. This prompted a cycle of disinvestment in many of Durham’s neighborhoods, fewer businesses, a deteriorating quality of life, inferior schools, increased crime and fewer residents, Norton explained.

Recent interest in downtown Durham has driven up prices in these nearby neighborhoods, leading to the displacement of former residents who are priced out.

“Gentrification is different than revitalization,” Norton said. “Revitalization is ground up and benefits most if not all members of the community. There are definite winners and definite losers [with gentrification] so it is a social justice issue.”

Her presentation cited statistics showing the average price per square foot of housing has shot up by more than 100 percent in several central Durham neighborhoods. The Cleveland Holloway neighborhood’s pricing has increased by nearly 500 percent in the past 10 years. Some of the new residents use a historic preservation tax credit to finance their home renovations. Another force behind the increase, Norton noted, is global financial firms that have found opportunities to make more money in the real estate market of growing communities than in the stock market.

“I see the effects of gentrification when it comes to rental properties with how it’s displacing a lot of low wage workers into the shelters and the hotel chains,” Durham resident Nigel Brown said.

Brown, who works with Housing for New Hope—a local nonprofit that helps re-house homeless people—noted that he hopes conversations will continue beyond the evening to create solutions.

“I came to really understand what we can do as a society to stop gentrification and redefine what revitalization means,” he said.

Norton said she felt hopeful for the future, noting that several parcels of publicly-owned land downtown could be dedicated to affordable developments. She also emphasized supporting community land trusts as a means of preserving long-term housing options for low and moderate-income families. The Durham Community Land Trust, which has been in operation since 1987, sells or leases property to families at affordable prices, providing more than 200 units of housing to residents in the area.

“I’m not cynical about the future,” Norton said. “Ultimately, what it comes down to is having lots and lots and lots of conversations across Durham about what we value, who we value and what actions we are willing to take to make those actions a community priority.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Adam Beyer is a senior public policy major and is The Chronicle's Digital Strategy Team director.