Duke had a watershed year in 1963.

That year, the University ushered in a new president, Douglas Knight, as well as its first five black undergraduate students. Fifty years later, three of these five returned to Duke to reflect on a half century of racial progress.

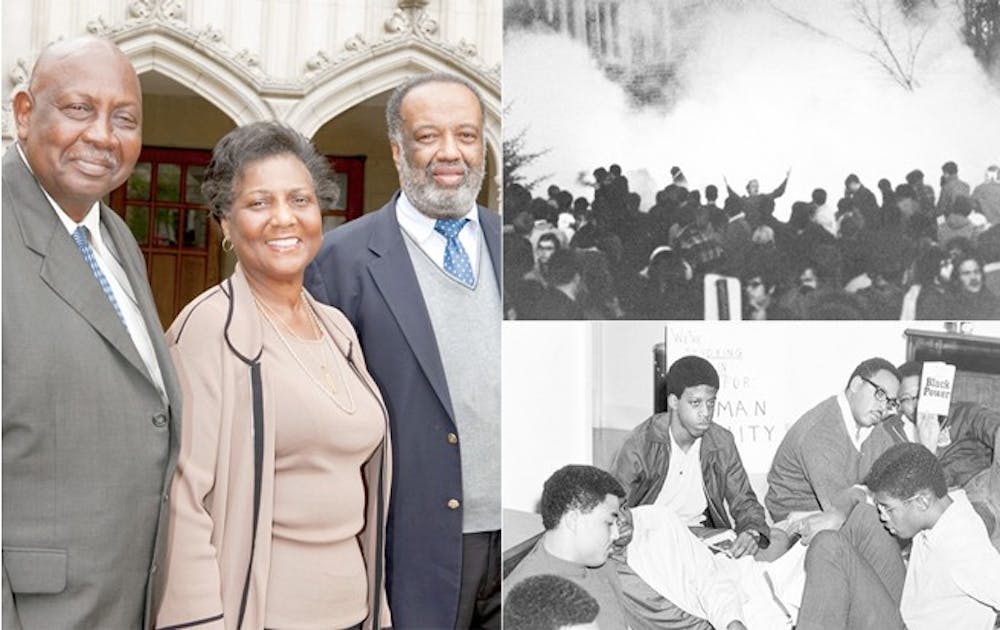

Gene Kendall, Engineering ’67, Wilhemina Reuben-Cooke, Woman’s College ’67, and Nathaniel White, Trinity ’67, were among the first class of black undergraduates. They reunited Thursday at Forlines House to discuss their Duke experiences. As they recalled it, their integration at Duke went surprisingly smoothly.

“There were no outward expressions of difficulty [with our presence],” White said.

Despite the common assumption that the students would have faced strong adversity, given the racial tensions in the 1960s South, the Duke community seemed very prepared for integration, White said. He thought it seemed as if administrators had had a conversation with all Duke community members in anticipation of the students’ arrival.

Professors were among their closest allies on campus, Reuben-Cooke said, noting that faculty members were so supportive that it was difficult to think of one specific act of kindness.

“People were aware of what we were going through,” Kendall said, recalling a gym attendant who pulled him aside to tell him about the assassination of John F. Kennedy. “He told me as if he knew it would touch me—and he was right.”

The three alumni, who said they are still friends to this day, agreed that their time at Duke changed their lives for the better. Although they all came to Duke from high-achieving but segregated high schools with high academic standards, Kendall recalled that members of the Duke community worked hard to provide him with fundamentals that prepared him for success in his later endeavours.

“You can do anything you want to do if you are willing to put forth the effort and try,” he said. “What the Duke experience did for me, was that it demonstrated to me that I had the wherewithal to get through any situation.”

Kendall transferred to the University of Kansas after his sophomore year and graduated with honors. The alumni panel also emphasized that it was not only students who gained from integration.

“When we first came [to Duke] it was assumed that we were the ones that were going to benefit from being in this environment. But it is very much a two way street,” White noted. “It wasn’t just a lesson to us—it was a lesson to the institution.”

White went on to explain that by maximizing the participation and abilities of a diverse Duke community, the University can benefit as a whole. To deny higher education to a select demographic is to limit the achievement of the society as a whole, he noted.

“It would seem to me very difficult to produce graduates who are effective on the world stage without having the world stage here,” White added.

Although they left a mark on Duke’s history, the three alumni downplayed their actions in deciding to enroll here.

“It’s not that we were special,” Reuben-Cooke said. “It [was] the time.”

Reuben-Cooke, an emerita member of the Board of Trustees and recipient of Duke’s Distinguished Alumni Award, expressed great satisfaction with the University in its current state as it pertains to diversity. Although the Duke and the Durham community have had a history of racial discrimination, she urged students to view this history as a call to service, not something to bring shame.

“Yes, we have racial issues, you can’t deny it here in North Carolina. And there’s an attentiveness to that,” Reuben-Cooke said. “Duke has a unique opportunity to make a difference because of its past. Our past is an incentive and an opportunity to make a difference.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.