Dr. Anil Potti has focused much of his research on developing genomic approaches that promise to help doctors find better ways to fight cancer.

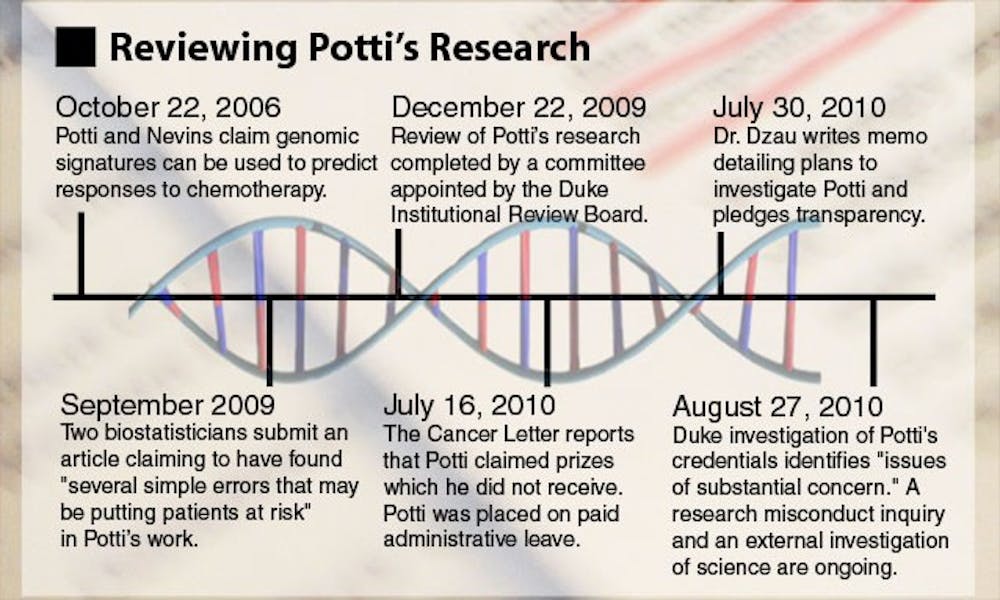

In 2006, Potti and a team of researchers introduced a new method of predicting how individual patients would respond to chemotherapy drugs based on genomic tests. In many cases, doctors may not be able to predict which cancer-fighting drug a patient will respond to best, but Potti’s approach, published in the Nature Medicine journal, potentially offered a solution.

Potti, an associate professor in the Department of Medicine and the Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy, and his collaborators described genomic signatures, or models they had developed that could predict individual patient responses to various chemotherapeutic drugs. In addition, they claimed to have developed a strategy to create a treatment plan “in a way that best matches the characteristics of the individual,” according to the paper.

“Part of what people are really trying to do in cancer therapy is [figure out] how can we decide ahead of time what is the best therapy for a given patient,” said Gary Rosner, director of Oncology Biostatics at Johns Hopkins University’s Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center. “That would be a really big step.”

Concerns emerge

Soon after the paper was published, however, biostatisticians Keith Baggerly and Kevin Coombes became concerned with the validity of Potti’s work.

Several doctors at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center were excited about the clinical implications of Potti’s findings, Baggerly said—specifically, that doctors would be able to predict patient response to certain chemotherapy drugs.

“A few of them came to us in bioinformatics and asked us to help them understand the details of how [the method] works so they could implement it and treat patients better,” he said.

But upon reviewing the experiments, Baggerly and Coombes, both associate professors of bioinformatics and computational biology at MD Anderson, found many of the details vague, which made it difficult to replicate Potti’s findings.

“One of the difficulties is that in many of the journal articles in this field, the descriptions of the methods that actually go into the papers... just don’t have enough detail to figure out exactly how the data were analyzed,” Coombes said.

In the next three years, Potti and his mentor, Joseph Nevins, director of Duke’s Center for Applied Genomics and Barbara Levine Professor of Breast Cancer Genomics, published a number of papers, including one in The New England Journal of Medicine, using methods similar to the first paper.

Baggerly and Coombes continued analyzing the research—spending about 1,500 hours in all—and found additional problems, including ones they said might jeopardize patient safety. In addition, they learned that other principal investigators had been running clinical trials for two years using data from Potti and Nevins that Baggerly and Coombes believed was flawed.

“We had found flaws with not just one but several of the papers [that were] somewhat simple in nature but important in outcome,” Baggerly said.

Baggerly noted as an example that the Duke researchers had reversed labels signifying whether or not a patient was sensitive or resistant to a chemotherapy in several papers.

“Clinically that means if they are making this type of mix-up with the real data, they would be suggesting instead of the best therapy for a given patient, the worst,” Baggerly said.

The two biostatisticians submitted their concerns in a September 2009 paper that later appeared in the December 2009 issue of Annals of Applied Statistics, also noting two other areas of concern.

Potti and Nevins indicate that several genes are important, but Baggerly and Coombes could not detect those genes using the software and data that Potti and Nevins said they used. In some cases, these genes were discussed in the paper as being key to the findings.

“They’re the ones that get put in the discussion of the paper saying this is why you should believe it, and those are the ones that do not reproduce at all,” Coombes said.

The second issue has to do with the scrambling of multiple labels in a way that improved the research findings.

“The labels as to who responded and who did not respond to the drug are scrambled in a way that makes the results that they find better than the results that we find,” Coombes said. “And you can tell this because... these are public data sources—you can compare what they posted on the Duke website with the original source of the data.”

After Baggerly and Coombes published their critique of the research, the National Cancer Institute contacted Duke about three clinical trials the University was running based on Potti’s and Nevins’s research.

The NCI’s concerns were brought to the Duke Institutional Review Board, and in early October 2009, the IRB launched an investigation of Potti’s and Nevin’s research, temporarily suspending enrollment in the trials.

Sally Kornbluth, vice dean for research, said the patients who were already in the trials continued their chemotherapy treatment upon advisement by several directors of other cancer centers.

“[We asked], ‘Would you take patients off of chemotherapy if they were already treated?’ and they said they would not take patients off of chemotherapy,” Kornbluth. said.

The investigation begins

In response to the NCI, Duke officials decided to engage outside reviewers to objectively evaluate the research, Kornbluth said.

According to The Cancer Letter, the IRB turned to three directors of other cancer centers and an independent panel of biostatisticians who were recommended by Kornbluth and Dr. Michael Cuffe, vice president for medical affairs, after consulting with the NCI.

Kornbluth and Cuffe declined to provide the names of the reviewers due to a confidentiality agreement with them, Cuffe said, adding that the agreement allowed the reviewers to speak for or against the research without repercussions.

“We wanted them to be able to say that [Potti and Nevins] were wrong, and say it freely, if that’s what they truly believed,” Kornbluth added.

The reviewers were tasked with making sure that Potti and Nevins had addressed all of the published concerns by Baggerly and Coombes and determining whether the methods remained valid in the context of the clincal trials, according to the IRB report obtained by The Cancer Letter. The reviewers could communicate freely with Potti and Nevins and had complete access to their lab, Cuffe said. They concluded that although Potti and Nevins could have better described their methods in their papers, they had adequately addressed all concerns raised by Baggerly and Coombes.

According to the reviewer’s report, they concluded, “the approaches used in the Duke clinical predictors [were] viable and likely to succeed.”

When the review ended, Kornbluth said she and Cuffe reviewed and interpreted the report, spoke with the outside reviewers as well as the NCI and other “knowledgeable bodies in [the] field” before consulting the principal investigators running the trials. After reviewing the report, the investigators elected to restart the three trials, she added.

Cuffe noted that the patients were informed of the investigation and agreed to stay in the trial.

“All the patients were reconsented, so they had all the same information we had,” he said.

More questions raised

Since the conclusion of the IRB investigation, additional issues have been brought forward, including more concerns raised by Baggerly and Coombes in The Cancer Letter, allegations from University of Michigan researcher David Beer that Potti improperly obtained and published Beer’s data, as well as a July 19 letter of concern signed by 33 other statisticians. In the letter, the statisticians expressed objections to the reinstatement of the clinical trials, noting the “the inability of independent experts to substantiate [claims made by Potti and Nevins] using the researchers’ own data.” They wrote it was “absolutely premature to use [their] prediction models to influence the therapeutic options open to cancer patients.”

But the researchers should not have expected to be able to replicate the research, because the methodology reported by Potti was unclear, Cuffe said. Unlike the outside reviewers consulted by Duke, other scientists did not have access to Dr. Potti’s lab.

In July, Potti’s credibility was again called in to question when accusations that he falsified portions of his resume appeared in The Cancer Letter.

“That changed, in my mind, the balance of the equation,” Cuffe said. “I will acknowledge that when someone has allegations of misrepresentation in one part of their professional life, to me that raises concerns about misrepresentations in other parts of their professional life.”

The clinical trials were once again suspended and Potti was placed on paid administrative leave from the University. Last Friday, an internal investigation found “issues of substantial concern” with Potti’s resume, according to a Duke News release.

The University will not make a final decision about Potti’s status as an employee until an internal research misconduct inquiry and an external review of his science have been completed. The research misconduct inquiry may consider whether Potti was intentionally dishonest or made unintentional errors. It may also look into whether Potti submitted false information in his grant applications.

A representative for the Institute of Medicine confirmed that IOM is considering conducting the external review.

This story has been modified to reflect that trials were being run by other principal investigators based on Dr. Anil Potti and Joseph Nevins's data. The original story incorrectly stated that Potti and Nevins had been running clinical trials for two years using data from their research.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.