Ending six straight years of rapid growth, the University’s investments dropped sharply in the past fiscal year, according to Duke’s most recent financial statement, presented to the Board of Trustees Friday.

Although the contours of the endowment’s 27.5-percent drop and the University’s efforts to cut $125 million from the budget have been known for several months, the 2008-2009 Financial statements provide the clearest picture to date of the recession’s effects on Duke’s financial situation.

According to the unreleased document obtained by The Chronicle, which covers the period from July 1, 2008 to June 30, 2009, the University’s net assets decreased 29.1 percent from more than $8.6 billion to more than $6.1 billion, largely because of investment losses. The statement will be released publicly online in about a week. The statement reported that the endowment and other investments provided 18 percent of the University’s $1.91 billion in revenue, or income, in the 2009 fiscal year—about the same proportion as tuition and fees. Just under half of Duke’s revenue came from grants and contracts, and another 5 percent was provided by donations. While revenue from investments and contributions declined, income from grants and contracts as well as tuition and fees rose slightly from their 2008 levels.

“The biggest problem obviously is the decline in assets,” said Executive Vice President Tallman Trask, the University’s chief financial officer. “Assets in one form or another generate income to the operating budget.”

Long-term pool dive

Perhaps the most-watched facet of University finances is endowment values. And Duke’s endowment, like the endowments of many other top-tier universities, declined sharply in the past year, as did the other pools of money controlled by the Duke University Management Company. DUMAC is a private firm that has handled Duke’s investments since 1990.

The endowment’s value fell 27.5 percent, from just over $6.1 billion to more than $4.4 billion, during the 2009 fiscal year as a result of spending and a 24.3-percent investment loss. These figures take into account about $500 million in investments that function as part of the Duke endowment but are held by other entities, mostly the philanthropic Charlotte-based Duke Endowment.

“Looking at the current economic climate, we feel confident in the manner in which DUMAC is managing, investing the University’s resources,” said Board of Trustees Chair and Democratic state Sen. Dan Blue, Law ’73. “We don’t expect there to be miracles.”

Duke spends part of the endowment each year to fund operating expenses. The amount of the endowment that the University can spend is determined based on the average value of the endowment over the past three years, so spending changes lag behind the endowment’s performance.

After endowment spending rose to $250 million in fiscal year 2009, it is projected to fall in the current fiscal year and at least through 2012, Vice President for Finance Hof Milam said.

Duke’s endowment drop in 2009 is similar to losses suffered by several other universities with large endowments. But it is much larger than the median loss of 17 percent reported in the same period by endowments with assets of more than $1 billion, according to the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service—an index compiled by the investment consulting and services firm Wilshire Associates.

In fiscal year 2009, Harvard University’s endowment fell 27.3 percent to $26 billion, the Harvard Management Company reported in its endowment report, and Yale University’s endowment fell about 30 percent, the New York Times reported Sept. 10.

Duke, however, has posted better long-term returns than almost any other university, said Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations. The University’s endowment rose an average of 10.1 percent a year for the decade ending June 30, 2009, besting Harvard’s 8.9 percent average annual gains in the same period.

Michael Brandt, professor of finance and finance area coordinator, said Duke’s high long-term returns are due in part to the riskier strategies DUMAC managers have pursued.

“Typically, higher expected returns are associated with higher expected risk,” he said. “There’s a premium that Duke earned from having taken a little more risk.”

Duke’s investment losses are not limited to the endowment. The long-term pool of investments managed by DUMAC—which Milam said includes about $1 billion of hospital assets and $1.1 billion of school reserves as of June 30, 2009, as well as the endowment—had fallen 26.3 percent to $5.97 billion.

“It’s the long-term pool hit that really has the greatest impact on revenue,” Milam said.

Duke’s pension plan investments are also managed by DUMAC, but separately from the long-term pool, Trask wrote in an e-mail. The pension plan’s assets dropped 27.4 percent in the 2009 fiscal year, to $946 million, as a result of $327 million in investment losses as well as pension payments for retired University employees.

Trask said the plan is still over-funded by $235 million, taking into account about $18 million in costs associated with the early retirement of 295 employees as of Aug. 31.

Taking risks, making money

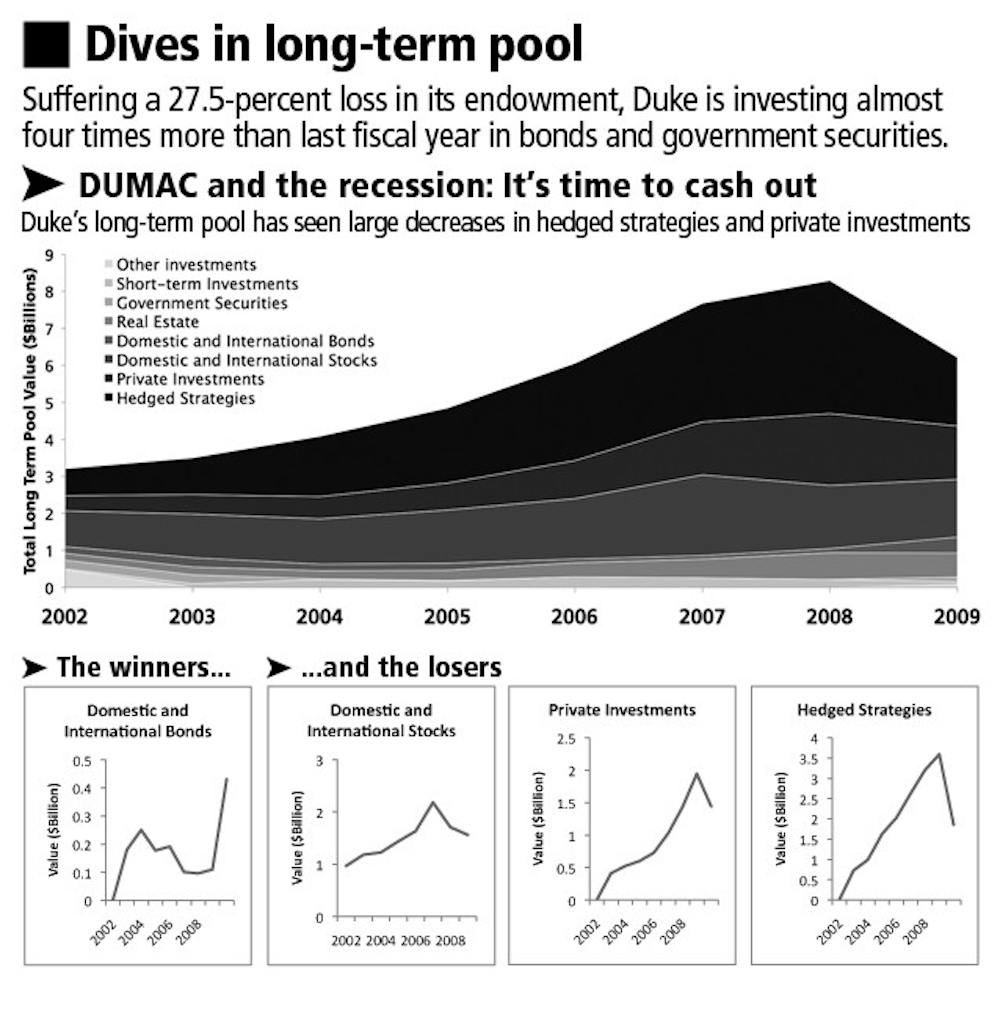

As Duke’s investments declined during the 2009 fiscal year, the proportions in different kinds of investments, such as hedge funds, bonds and stocks, changed considerably. These changes have generally reduced the risk of further investment loss and increased the availability of cash, or liquidity.

Trask said the investments in the long-term pool have become more liquid than they were 10 months ago when Duke borrowed $500 million to increase its available cash.

“Historically, the endowment world was not too concerned with the year-to-year liquidity,” said Brandt, whose research interests include asset allocation and risk management. “This whole operational liquidity issue is something that needs to be rethought and taken into account.”

Trask said Duke has also increased its liquidity by shifting some investments into bonds and government securities. Duke’s investments in bonds almost quadrupled in 2009 from $110 million to $430 million. In addition, Duke put $124 million in U.S. government securities, or debt, after carrying no such debt since 2005.

Bonds and securities composed 9 percent of Duke’s 2009 portfolio, after making up just 1 percent a year earlier. These assets, known as fixed income investments, are often less risky than Duke’s other investments, Brandt said.

Diane Vazza, managing director of global fixed income research at Standard and Poor’s, said Duke’s shift into bonds was a smart move, so long as the University has bought mostly highly rated bonds, also known as investment-grade bonds. Higher bond ratings indicate that the company issuing the bonds is more likely to be able to repay its debt.

“There are some very good, solid, investment-grade corporate credits, so that would be a good mix in your asset allocation,” she said. Duke releases little information about the types of bonds it owns, but Trask said the University owns mostly highly rated bonds. He added, however, that 1 percent of bonds in Duke’s portfolio have a “C” rating, which indicates a high risk the companies that issued the bonds will not be able to repay them.

The biggest drop in the portfolio was in hedged strategies, which declined from 44 percent of an $8.1 billion portfolio to 31 percent of a $5.97 billion pot in fiscal year 2009.

Real estate and private investments each occupied about the same proportions of the portfolio in 2009 as in 2008.

Brandt said based on information in the financial statement alone, it is difficult to fully assess DUMAC’s investment choices or level of risk.

“In order to truly [determine the level of risk], you’d need to talk to them or see that kind of calculation,” he said. “It’s hard to second guess them on the basis of their asset allocation.”

An executive assistant at DUMAC said officials declined to comment. Trask said DUMAC will sell some of its bonds and move into other investments when managers think the time is right. He said the lower returns generated by bonds and securities are preferable in the short term to other investments, which may continue to lose value.

“I don’t think you’re going to see them jumping after a lot of illiquid investments any time soon,” he added.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.